In this book, comedy and narratorial gusto are frequently combined with terror or border on despair

Lyuba, who cooked for the workers responsible for the clean-up at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant following the catastrophe of 1986.

All right, perhaps it’s time to tell you something about the food?

I’ll tell you one thing, Witold. Although I was a cook, and although I’d worked at a power station and also at a good restaurant before, never in my life had I seen such an abundance of good food as at Chernobyl. As if the state wanted to reward the people for sending them to such a dreadful place. Go and die, but have a nice feed first.

There was a whole sea of produce there. Little cubes of butter, full fat cream – it sounds funny, but in those days, under Gorbachev, that was a real delicacy – strawberry, blackcurrant and cranberry compote, on top of that there had to be a Soviet drink called mors [made of lingonberries and cranberries], and to eat there was aspic, meat, ham, sausage, sea and freshwater fish, smoked, roasted, any way you liked. And all sorts of fruit: watermelons, melons, oranges, pomegranates from Azerbaijan. As a kind gesture, a fellow from Italy sent us two railcars full of lemons, so every day we made lemonade.

The menu was drawn up for us by food technologists to provide the right number of calories. And there was plenty of cooking. Goulash, salads, compotes, pizzas, cheesecakes, meat rolls. Various soups, including pea, buckwheat, Ukrainian borscht, Russian borscht, all required to include meat of course, to give strength. And if we had the time and the energy, we made pancakes or baked buns.

Each person was given a glass of cream too – apparently calcium helped against radiation, so there was also a lot of tvorog [curd cheese] and other cheeses. In spite of which, everyone believed vodka helped the most. I was convinced it helped against radiation, and although I’m not a drinker, every day before work I forced myself to drink a shot of it. […]

Gradually other canteens began to open near ours, at similar pioneer camps, and Valentina thought up the idea of competing with them. We all sat down together and discussed what we could do, what these people needed. And we devised a plan to set up a table the length of the room laden with all the healthiest foods, so they could help themselves to dessert and enjoy the sight of it all at once. We wanted to give them some comfort, we knew it wasn’t easy for anyone, but even in the most dreadful times if you eat well, you’ll feel better for a while at least.

So we did it – we set up three tables end to end the length of the dining room, we called it the Vitamin Table, and every day it was a point of honour

for us to make it look as beautiful as possible. What wasn’t there? Raya made little roses out of pearl onions dipped in sugar, it looked lovely. I carved carrots into flower shapes. There were also little hedgehogs with pickled apples on their backs. And large thermos flasks filled with digestive teas made with Siberian herbs. Everything was pure, fresh and delicious.

We worked so hard our hands were sore and our eyes stung. One time I was so sleepy that I went to work without any shoes. But everyone who came to our canteen left satisfied.

Excerpt translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

In this book, comedy and narratorial gusto are frequently combined with terror or border on despair

Translation rights: Andrew Nurnberg Associates, anna.rucinska@nurnberg.pl

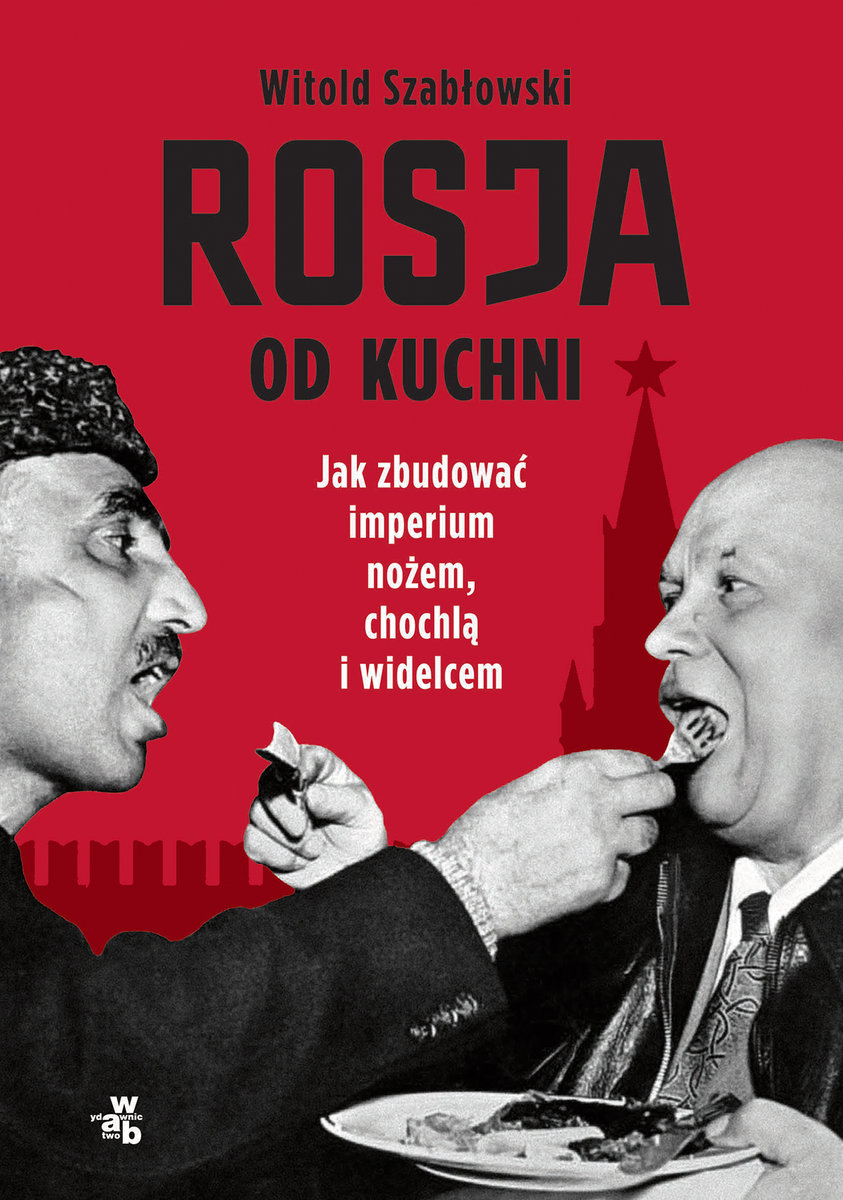

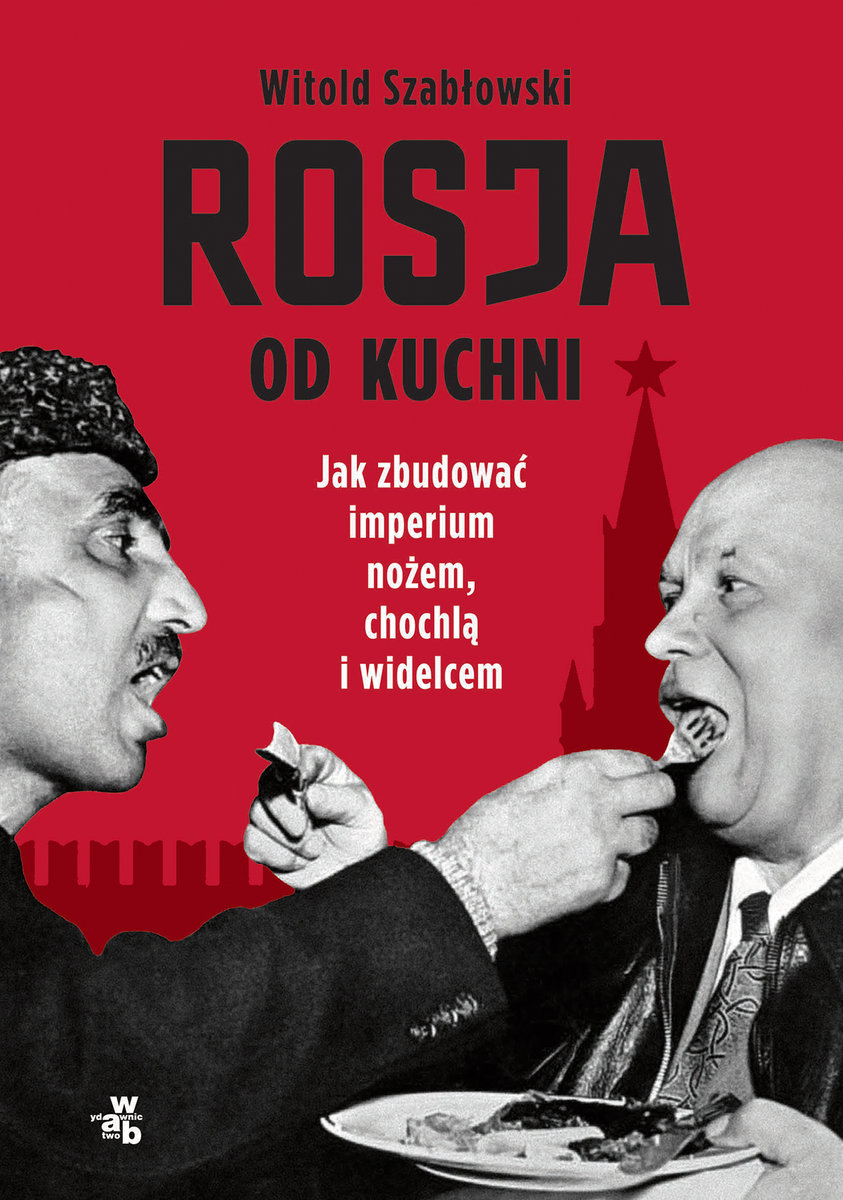

Foreign language translations: Rights for Rosja od kuchni. Jak zbudować imperium nożem, chochlą i widelcem have been sold to the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Slovakia, Spain, Taiwan, Ukraine and the USA. Szabłowski’s other works have been published in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Taiwan, the UK and Ukraine.

At first glance What’s Cooking in the Kremlin looks like a frivolous book, easily mistaken for a culinary guidebook, or just a recipe book, featuring various forms of Russian cuisine. The author really does include recipes at the end of each chapter for some of the dishes that appear in the stories he tells. But naturally, a seasoned author of reportage of Szabłowski’s calibre is merely using the convention of “lifestyle” literature for his own purposes, and there’s something perverse about this subtle game. Because this journey through tastes and flavours is a way to present the nightmare of the darkest episodes in Russian twentieth-century history. In this book, comedy and narratorial gusto are frequently combined with terror or border on despair. A description of the grand splendour of the tsar’s dinner table merges into an account of the assassination of the last Romanovs. The colourful abundance of Georgian culinary tradition cannot be separated from an attempt to understand the life of Stalin. Readers are likely to feel that Szabłowski is leading them along a tight-rope, taking them on an expedition where there’s a fine balance between the lightness of food writing and the gravity of historical reportage. In this way Szabłowski is continuing the adventure he began with his previous bestselling book, How to Feed a Dictator. In both books he masterfully combines the opposite poles of cookery and crime. And yet What’s Cooking in the Kremlin reveals an entirely new world of facts and incidents. Szabłowski travels to Russia in search of witnesses to the most significant, but also the most traumatic episodes in the history of twentieth- and twenty-firstcentury Russia, from the reign of Nicholas II to that of Vladimir Putin. He meets people who cooked for the country’s rulers or their descendants, and talks to members of the inner circle of inaccessible Kremlin leaders, giving us a unique opportunity to learn about Russia from an unfamiliar angle. But the war in Ukraine makes this book even more acute and timely than it might have been. Superbly written and hard to put down, it is an unquestionably successful attempt to face up to the demons of imperialism. I can recommend following in Witold Szabłowski’s footsteps as he tries to understand Russia and its empire through the kitchen.

Jakub Moroz

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”