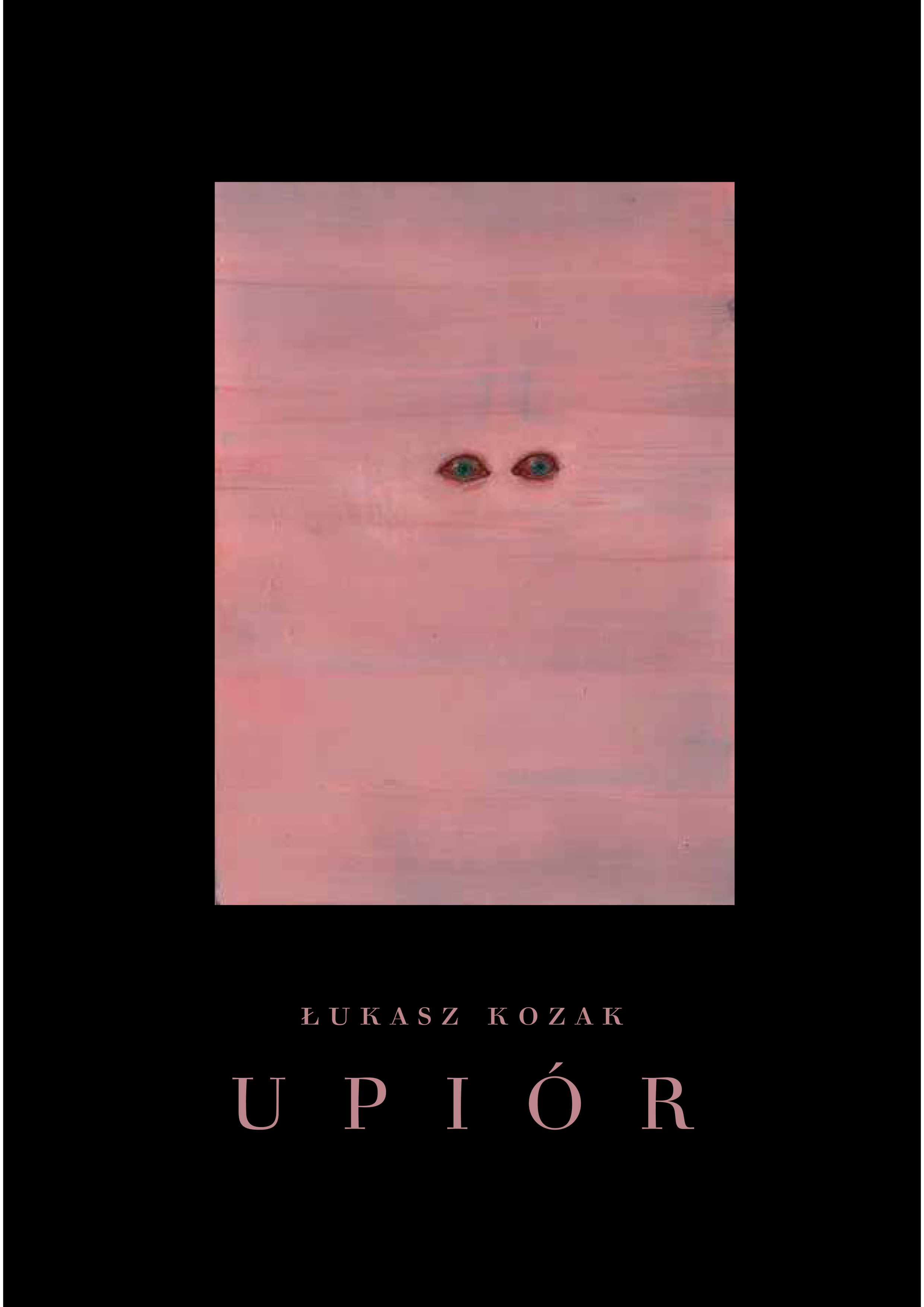

A masterful work on the upiórs – the primeval Slavic vampires who have haunted Polish literature and history for centuries

This book you hold in your hands is very different from the one I originally set out to write. I was in the process of collecting sources on Polish folk beliefs for English-language readers (published as With Stake and Spade: Vampiric Diversity in Poland). The task ahead was simple, I told myself. It would suffice to translate materials collected by Oskar Kolberg and publish them with Benedykt Joachim Chmielewski’s New Athens and Franciszek Bohomolec’s Devil… maybe throw in some ethnographic curios for good measure. At the time, I still saw my subject matter – condescendingly – as a kind of poor man’s mythology or folk demonology. After all, this is how historians and ethnologists had framed it for generations. It was my curiosity that set me on a path uncharted by scholars. I started perusing old newspapers, judicial decrees, theological treatises and the marginalised testimonies of Ukrainians and Kaszubians. Only then did it dawn on me that it was anti-mythology I was dealing with. This was a record of real events – the lives, deaths, emotions and actions of actual people, flesh and blood. Official history had spurned these people, and scholars had discounted their stories. I finally grasped that the tale I was tracing could not be reduced to “myth” but nevertheless constituted the essential or even only myth of the Slavic people. So I cast aside my academic training and taught myself to listen, patiently and reverently, to the voices of the dead. Thus, Upiór was born.

From that point onward, the book took shape during an unusual time. At the onset of the pandemic, I was writing of undead corpses carrying plagues. Right as I was writing a chapter on romantic revolutionaries, social movements erupted worldwide to overturn the status quo. Several days before writing even these words, voices spoke of the “end of history” – a history told in endless refrain, as if out of spite, and always resisting closure. If this book alters how we view our history, even in some small way, then I will feel rewarded for my efforts. For history does not end. The book lies open. It is only our perception and interpretations that change, and this is a process we should face willingly and without fear.

Buried Superstition

At the dawn of the 19th century, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist. It had been the great project of modern political thought: a multicultural federation spanning territories today shared between Poland, Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania. Here, a diverse abundance of ethnic and cultural influences coexisted and intermixed. Poland’s loss of sovereignty and figurative demise provoked reactions far from uniform, from armed struggle to expedient reforms to ambivalence or even preference for the new situation and attempts to adapt. This transformation coincided in time with a great wave of triumph and relief shared by the disappearing nation’s intellectual elite: a prodigious folk belief had been vanquished, and in its place emerged reason and the radiant knowledge of the Enlightenment (albeit delayed by several decades).

Members of the newly “enlightened” took heart that they had defeated belief in a being more feared than the devil, hell, or even God himself. Believers, nonbelievers, crypto-atheists, deists, followers of Voltaire and Descartes, bishops and ex-Jesuits – all of them grappled with this entity. Now equipped with theoretical tracts, scientific, philosophical and theological arguments, sermons, poems and plays, they derided this superstition and scorned all who clung to it as unenlightened simpletons.

This creature that united the sharpest minds and pens of the Polish Age of Reason was the upiór: undead spirits risen from the grave who raided humans and cattle, suffocating them or drinking their blood, spreading plagues and overturning the world order with their very existence. The upiór was chaos embodied, and belief in this figure was the bane of theologians and a menace to philosophers.

Excerpts translated by Eliza Rose

A masterful work on the upiórs – the primeval Slavic vampires who have haunted Polish literature and history for centuries

Translation rights: Fundacja Evviva L’arte, izabela.a.michalska@gmail.com

Is it possible for a work of literary history to match the allure of a bloodcurdling horror novel? Of course, but under one condition: that it is penned with the brilliant style and staggering erudition with which Łukasz Kozak has written his masterful work on the upiórs – the primeval Slavic vampires who have haunted Polish literature and history for centuries. Drawing from an immense range of archival curiosities and excerpts from the press, Kozak leads us through centuries of Polish history to introduce us to the figure of the upiór. Legendary creatures commingle with those who are only too real and whose macabre deeds exceed the bounds of humanity. Upiór begins with early Slavic folk beliefs dating to the Polish nation’s origins and ends in the present day with its lingering traces of bygone myths.

With Kozak as our guide, we visit courtrooms where the trials unfolded of criminals so inhuman that they were declared to be upiórs. We encounter folk methods for combatting supernatural threats that can endanger anyone at any time and in any place, be it a Polish city or the Ukrainian steppe. We are also treated to the author’s speculations about the obsession with upiórs that swept over the great bards of Polish Romanticism and its far-reaching influence on Polish culture and spiritual life.

Accompanying the book are fantastic illustrations by the acclaimed Polish painter Aleksandra Waliszewska, whose scintillating images of the demonic and occult capture the upiór-haunted psyche. The inquisitive reader eager to expand their knowledge of Poland’s vampire-upiór lore has much to gain from this rich range of source materials compiled and explored by Kozak.

Marceli Szpak

Translated by Eliza Rose

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”