Although time is merciless, some survivors still live in the enclaves of their memories

The metal flap with the inscription „Briefe und Zeitung” opens a crack, revealing a slot for the postman to shove in the mail and the newspaper. In a house on the outskirts of Piaszno – once situated a few kilometers from the border, albeit on the German side – a solid wooden door separates the brick porch from the main body of the house. A semicircular window in the house’s sloping roof of ceramic tile looks down on visitors. A red-brick chimney climbs high into the sky. Outside, only the plastic PVC framing indicates that time has not stopped here and that the mail delivered daily to the household is no longer in German. The present owner, Urszula Landowska, takes small steps to cross the living room, pushes a heavy wooden chair away from the wall and slumps into its soft cushion. On the day of her birth in 1938, German border guards strolled around this room. Her father was a staunch communist who put up posters against Hitler in nearby Tuchomie. The locals were rather unimpressed by his views. They held him at gunpoint, threatened to kill him, and beat him up with a stake. The authorities watched his every move and when the war broke out, he got his combat boots from the Wehrmacht and was shipped off to Norway. During his absence, the communists had finally arrived in Kashubia. The old lady fixes her stare on the high-gloss tabletop.

‘Up to that point we lived completely normal lives, as if the war had never broken out. This was Germany. I was seven then, but I remember everything like it was yesterday. End of February 1945, bitter cold. At night, my mother dressed me in the warmest sheepskin coat and told me to climb on the cart because we were running away – first towards Słupsk and then Gdańsk. For three weeks I neither washed nor undressed. In the city we reached the port where a fishing boat was waiting for us. My uncle, my father’s brother, kept rushing us: „Hurry up, quick, before the boat sails away.” And it did sail away. A buzzing filled the air, black dots appeared in the sky, and bombs started to fall all around. Explosions, fire, flames. And thousands of people trying to board the great ship by the pier. Mostly women with babies, or kids my age, and old men. With suitcases, bundles, bags. Screams, panic.’

The woman gently strokes the lace tablecloth, moving the purple orchid closer to the middle. A calendar in Kashubian with photos from the entire region and a heart cut out of paper hang on a dark-brown tile stove standing in the corner. That winter they miraculously managed to board a ship to Germany and reach Bremen via Lübeck.

‘My mother and I were already feeling glad that everything would be fine after we had made it this far when the earth shook at night. Alarm sirens began to wail. The Allies were bombing the Germans. In a cellar, we lived to see the arrival of the English. One of them took my mother’s watch, while another wanted to rape her but stopped when the three of us kids started to yell hysterically.’

Due to exhaustion and frostbite, Urszula’s dad was taken from Norway to a military hospital where the end of the war found him. As soon as he recovered a little, he located his family in Dortmund thanks to his brother, and they tried to start a new life there. However, in 1947 they returned to Tuchomie to look after their ailing grandmother.

‘I couldn’t understand what happened here. It was Germany when we left two years earlier and then suddenly it became Poland. But I didn’t speak a word of Polish. Only German, with a little Kashubian. At church, I could only sputter three words, “Jesus”, “Mary”, and “amen”; at school, two: yes and no. Pretending to understand, I nodded my head while the teacher might as well have spoken Indian to me. The cover of the primer showed a doggy with the word “Ace” under it. So, I ran around the village shouting „Ace, Ace!” at every dog. Finally, a shopkeeper explained to me that „Ace” was a dog’s name while “dog” was a proper word for a dog. No one wanted to sit beside me at school because who would share a bench with Adolf?! The kids in the school yard kept calling me that.’

Excerpts translated by Mirek Lalas

Although time is merciless, some survivors still live in the enclaves of their memories

Translation rights: Andrew Nurnberg Associates Warsaw, anna.rucinska@nurnberg.pl

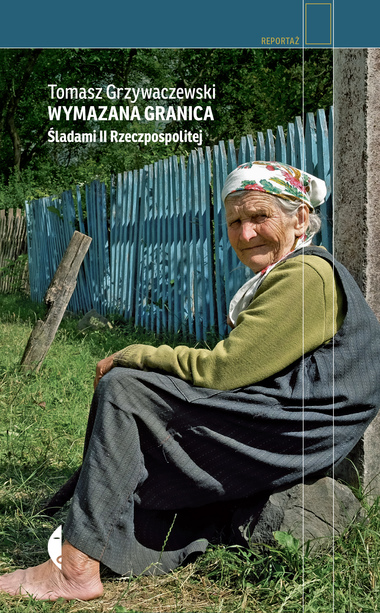

Wiped off the map by the joint German-Soviet aggression in September 1939, Interwar Poland never regained its former territorial shape. However, its 5,529 km border left a permanent mark not only on the European topography, but above all on the minds of the past and present inhabitants of the pre-war borderlands. Today the witnesses of the erased borders are eighty or ninety years old. Although time is merciless, some survivors – miraculously saved from the ravages of war and driven out of their homes in the former Eastern Borderlands – still live in the enclaves of their memories, while others might longingly remember Poland from the doorsteps of their wooden, Belarusian or Ukrainian shacks. Thanks to the author’s excellent reporting sense, the story features lively characters with identities shaped by the centuries-old tradition of the territories where languages and cultures met. In addition to venerable seniors, we also hear the voices of their successors who – though born in a different reality – still live in the shadow of the pre-war border. The local customs and architecture preserved the traces of that border. Terse details and concrete images, like the hands of an elderly woman smoothing out the oilcloth on a tabletop, or a strong local flavour conveyed through colourful setting description, stand out among many narrative techniques that turn Grzywaczewski’s reportage into a vivid and potent testimony. This is nonfiction at its best, giving the reader not only a sense of direct participation in the story, but also a chance to appreciate how it was constructed. Showing the mechanisms behind momentous historical events as struggles to move the border posts dividing barnyards produces very authentic images that stay etched in our memory.

Ireneusz Staroń

Translated by Mirek Lalas

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”