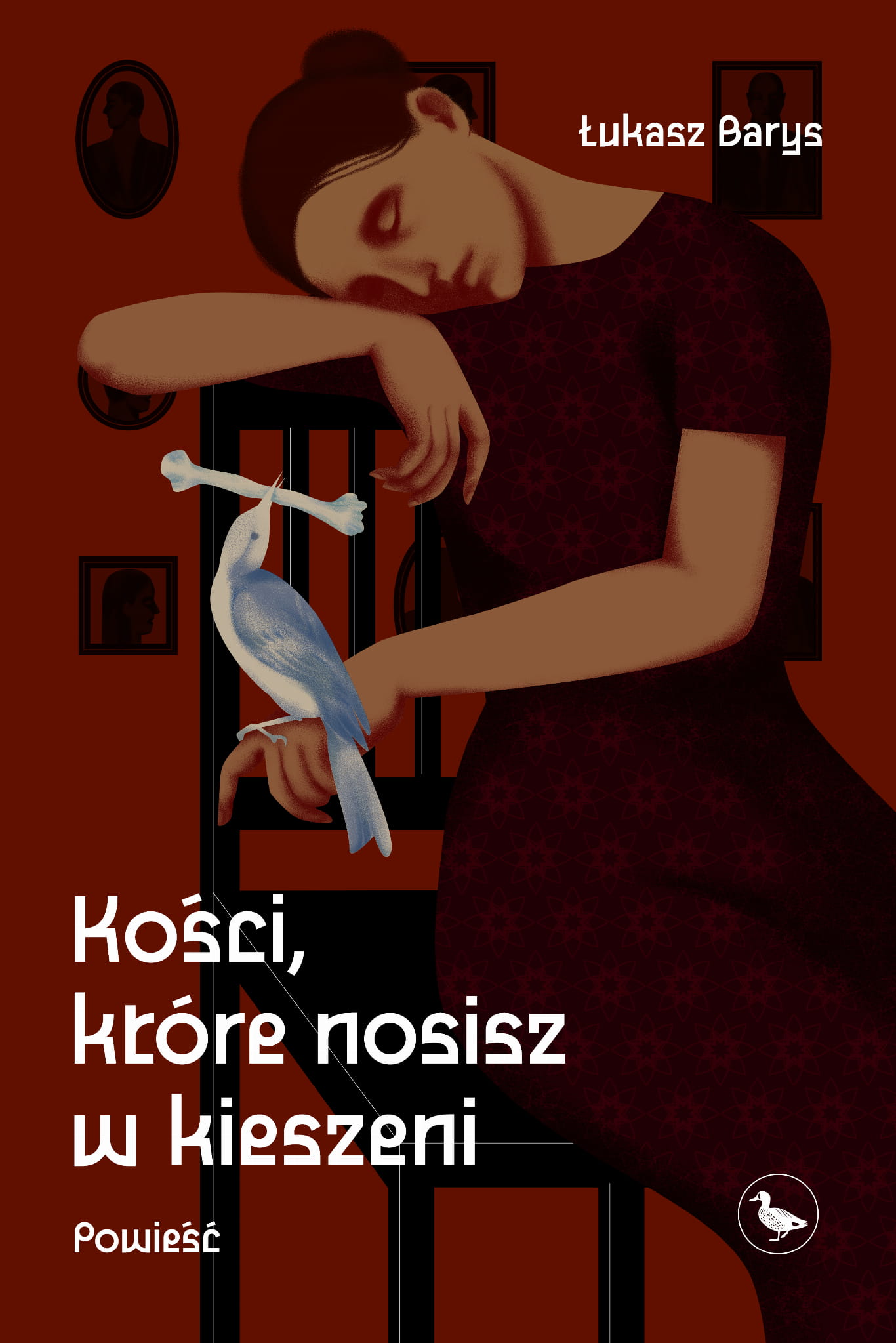

A debut that happens once in a decade

A few days earlier, I found some similar bones in Sonia’s pocket. The evening had caught us by the dirty, bare calves. I spent half the day drifting about the courtyard, until the orange sun slid across the concrete into the darkness. The holidays are always boring, the heat lays a hand over your mouth and you can’t make yourself do anything, everyone else is off vacationing. Mum was dozing after her shift at the market, Grandma was dozing because she’s old, it was up to me to haul my sister to the tub, though she wasn’t having it, she runs away bawling, screaming she can’t stand me.

I let her scream, hoping Mum would wake up and give her a piece of her mind, but she didn’t stir – she was sleeping off all those groceries she’d scanned. For her part, Grandma didn’t give a shit whether we stank or not, all her senses were pretty much clogged – her nose, her pores, her heart – after all, under that apron of hers was all death and disease, and that came before our hygiene.

Anyway, I grabbed Sonia by her frail wrist and pinched her until she finally calmed down – she could see there was no sense playing games. She was afraid of me, and that hurt, but I didn’t say anything, I took her and pulled the ice-cream-splattered shirt over her head and mussed her hair, which seemed oddly stiff, like wood chips. With my other hand I turned on the faucet and then poured a bit of soap into the bottom of the tub. Then I yanked down her shorts and wiped her bloody knees. Sonia’s toes and ankles were nearly black, she’d been walking around all day in sandals and playing with her dolls in the dirt.

“What kind of Barbie are you?” I asked. “A mole-Barbie?”

She didn’t respond, she balled up like a larva and crossed her arms over her protruding belly. Defenceless and scrawny, she was like a miracle in need of protecting, and I wanted to cry. But the water was still pounding away on the cast-iron tub and I had to turn it off – I’d heard enough in nature class about water shortages for animals and people, and from Mum about the bills that her supermarket wages never seemed to cover.

“It’s hot! It’s hot,” Sonia wailed, and I had to pour in a bit of cold. Then more, and some more, until the water was too cold for a bath, but my sister climbed in anyway.

“Why can’t you bathe by yourself? You’re big enough,” I snorted, reaching for the dirty clothes.

I tried cramming the clothes into the overflowing laundry basket, but then I touched something weird. (…) Sonia hadn’t been watching what I was up to, but when she did, she screamed for me to stop. It was too late – I’d managed to shake maybe a dozen brown bones into my open palm, and there in the bathroom it suddenly got unbearably stuffy.

“Where’d you get these?” I asked.

Again she was silent – instead of answering she leaned over the edge of the tub and threw up all over the pyjamas laid out on her towel. Hello Kitty crumpled under the weight of the girl’s vomit. I threw a towel over her. She only had the one pair of pyjamas, and now they were going to need washing.

“Go to bed,” I told Sonia.

As I was doing the laundry, I looked at the bones scattered near the toilet. Jumbled up like a jigsaw, they totally stood out. They were pretty broad, definitely not from poultry. They were speckled brown. I didn’t dare touch them again, so I just knelt by them and stared at the grooves and swirls carved into their surfaces. I found a plastic bag and went back to the washroom, cleaning up the dirt that was tracked in. I didn’t want to sleep, my head ached. I slipped the plastic bag with my trove under my pillow – I could feel it poking through. Sonia and Daniel had nodded off. I could see their dark silhouettes from my bed. I began crying, just like that, and I couldn’t stop. I cried and cried, and the bones lying nearby vibrated. I dreamed of them: I saw the earth outside our house, full of mingled human and animal bones.

Excerpt translated by Soren Gauger

A debut that happens once in a decade

Translation rights: Wydawnictwo Cyranka, konrad@wydawnictwocyranka.pl

For a long time, Polish literature shied away from portraying reality, especially in its small-town variety. Luckily, a few fresh new voices have cropped up in recent years, reclaiming this reality that was so ignored by the mainstream. Łukasz Barys’s debut joins this trend, and is also one of its finest exponents.

At only twenty-four, this prose writer and poet (already lauded and awarded) takes readers on an unsentimental journey to his home town, Pabianice. Though Barys’s talent for language can call to mind magical realism (despite the prevailing greyness), the reality here is far from magical – decay, misery and death reign supreme. Our main protagonist is Ula, a student at the local middle school. She lives with her grandma, who has one foot in the grave, and her mother, who works as a cashier and keeps bringing home new “daddies”. She also takes care of her younger siblings. Cemeteries give her a moment’s respite, and her sense of connection with the dead lets her forget a bit about the lack of warmth at home. Ula’s story lets Barys address several issues that are key to today’s discourse (in and outside of literature): class divisions, poverty and exclusion, but also a teenager’s personal struggles with their body and family. The main asset in Barys’s novel is the language, which is poetic, packed with metaphors and literary and pop-culture references, and firmly rooted in today’s Polish and real speech; his gentle irony and wit allow him to disrupt the funereal tone a bit. Debuts like The Bones You Carry in Your Pocket happen once a decade in Polish literature. Łukasz Barys is now working on his second novel. All signs seem to show that the coming years will be his.

Krzysztof Cieślik

Translated by Soren Gauger

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”