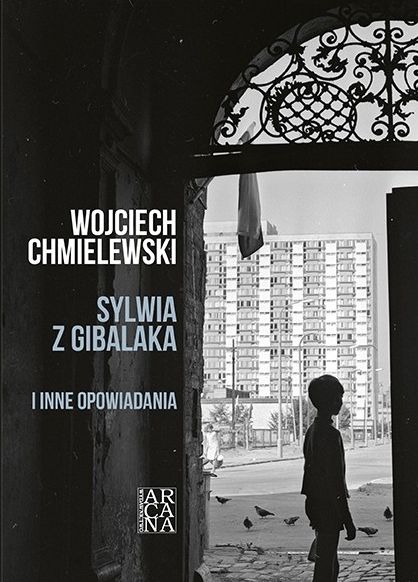

A magical portrait of Warsaw – a city of micro-events marked by great history

A magical portrait of Warsaw – a city of micro-events marked by great history

(For excerpt in Spanish, please, scroll down)

Hiding in his old neighbourhood is someone who’s lived there for many years and still can’t free themselves from it. On Perec Street in front of the electrical plant, he walks between the parked cars, peers at the wet, skid-marked asphalt and glances toward the grocery store, which for years has stood consistently at number 13/19. Many times he’d gone there to buy Cytroneta and drunk it on a sidewalk with a view of the cracked inselbergs from the ghetto, and where someone had scrawled on one of the dirty walls of the exposed stairwell: Sylwia of Gibalak.

He sometimes wondered, as he stood on the sidewalk, who this Sylwia was, but only rarely, for an instant. He was more worried about his father, who might get drunk again in the privacy of his own home and start lecturing. His glassy, vodka-soaked eyes exuded mockery and blame. They lurked there, scrutinising his appearance, his hairstyle, and then his father’s mouth would spit out some incoherent commentary that always came with a moral.

Sylwia of Gibalak, or rather the graffito “Sylwia of Gibalak”, haunted the wall for many years; it was too high up, the only things that could erase it were rain and snow, yet they didn’t manage to, even though it probably wasn’t written in ordinary paint, more likely a rag dipped in piss or something like that.

In class they knew his father was a hard drinker. His friends would draw cartoons of a drunk, he’d star in comics that got left on his seat. In one, clutching his ever-present bottle labeled “Rye 40%”, he joined in on diverting Russian missiles and a journey to the moon; another time he was a mediaeval knight charging at the tank from the show Four Tank-Men and a Dog.

He’d get into fights over it, he couldn’t let anything go. He’d come home black-and-blue, with the pocket torn loose on his blue, synthetic school smock. There, at home and with the TV on, a new advice bomb was waiting for him. There was also that bitch of a bio teacher. She had it in for him and was threatening to make him repeat sixth grade.

When the student on watch next to the steps shouted, “She’s coming!” the class would form up into orderly pairs in front of the lab.

“I beg your pardon!” she’d begin. “What does ‘she’s coming’ mean? Who is coming? A friend of yours?”

And then she’d go right the hell on:

“Idiot, don’t you care how your own body works, what you’ve got inside?” She was used to taking her anger out on them while nursing a coffee with three spoonfuls of sugar, which she brewed in the back room during class. Then the little network of red veins on both her cheeks would burn their brightest. A pendant hung from her wrinkled neck – a little coral elephant carrying a golden palanquin on its back.

He hangs around the neighbourhood backstreets, peeking into various nooks and crannies, into stairwells and trash cans; he’s in the courtyard by an apartment building on Grzybowska Street; there used to be a sandbox here, now it’s a parking lot. Sylwia of Gibalak, he never met her. Now he’s thought of her many times, passed the time wondering what she might have been like. A friend from the same stairwell told him once that over in Gibalak they hate snitches. And do you know what they did to one guy who ratted to the police? They cut off his legs. With a knife. And then you know what? They clamped it with some wire and that was that. This friend laughed cheerfully and finished his story by tucking his cigarette butt into an opening in a glass brick in the stairwell. He’d built up a pretty big pile there, it was an installation you could admire as much as you liked.

On Grzybowska Street and Waliców Street, in pre-war apartment houses with propped-up ceilings, time swirled around like the smoke from the Varsovin Factory, clouding the landscape in brown crap. As he wandered these alleys, he sometimes imagined this Sylwia. She definitely had dirty stockings and an ugly wool cap. Greasy hair, because in the barracks in Gibalak you got a bath once a week, when they warmed up the water in a coal heater, or you might not even get that, because everyone was lying around drunk.

He never met Sylwia, didn’t get to know her, didn’t see her, but she was there, after all, she lived somewhere in this neighbourhood that, although it seemed so well-tended – with a library on Chłodna Street, a church with saints standing in niches, a specialist clinic run by senior doctors – nevertheless contained a great deal of decay. The stench of it wafted over the grates masking cellar windows, which people threw trash into. There was probably a rotting dead cat or rat.

Translated by Sean Gasper Bye

***

SYLWIA DEL GIBALAK

En su antiguo barrio se esconde alguien que ha vivido aquí mucho tiempo y aún no puede liberarse de este lugar. En la calle de Perec, junto a la planta eléctrica, deambula entre los coches aparcados, se fija en el mojado asfalto y en las huellas de los neumáticos y dirige la mirada a la tienda de comestibles que desde hace años ocupa el bajo del número 13/19.

Muchas veces compraba allí una limonada y se la bebía en una acera desde la que podía contemplar los resquebrajados vestigios del gueto, en una de las sucias paredes de la escalera exterior alguien había garabateado: Sylwia del Gibalak.

¿Quién era esa Sylwia? Se lo preguntaba de cuando en cuando estando allí, en la acera, pero rara vez y sólo por unos instantes. Su cabeza la llenaba más bien el miedo a su padre, que quizá se habría vuelto a emborrachar en su sosegado hogar y querría darle una nueva lección. En esos ojos vidriosos y disueltos en vodka podía percibir las ganas de camorra e infinitos reproches. Estaban ahí, acechando. Primero examinaban su aspecto de arriba abajo, su peinado, y luego sus labios farfullaban un comentario al que siempre iba ligado un sermón.

Sylwia, la del Gibalak, o más bien la propia inscripción “Sylwia del Gibalak” siguió metiendo miedo desde esa pared durante muchos años. Estaba demasiado arriba y sólo la lluvia y la nieve podían borrarla. Y, sin embargo, no lo conseguían, aunque no había sido hecha con pintura común, sino quizá con un trapo impregnado de orín o algo así.

Los de su clase sabían que su viejo empinaba bien el codo. Sus amigos hacían caricaturas de un borracho, era el protagonista de tiras cómicas que ponían sobre su pupitre. En una de ellas llevaba en la mano su inseparable botella con la inscripción “Vodka de centeno 40%” y tomaba parte en el secuestro de un cohete ruso y en una expedición a la luna; en otra hacía de caballero medieval y se abalanzaba sobre “Rudy” 102, el tanque T-34 de la serie más popular del momento, Cuatro hombres del tanque y un perro ( Czterej Pancerni i Pies ).

Llegaba a los puños cada vez que ocurría, no podía dejar la cosa así. Volvía a casa cubierto de cardenales, desgarrado el bolsillo de la azulada bata escolar de material sintético. De vuelta a sus lares le aguardaba una nueva batería de admoniciones. Y además estaba la hijaputa de biología. Le había tomado manía y corría el riesgo de repetir curso.

—¡Que viene! —gritaba el alumno que estaba haciendo guardia junto a las escaleras, y esa era la señal para que toda la clase se pusiera en fila de dos delante del laboratorio.

—¡¿Pero esto qué es?! ¿Qué es eso de “que viene”? ¿Quién viene? ¿Vuestra amiguita?

Y luego seguía como una apisonadora:

—Idiota, ¿es que no te interesa saber cómo funciona tu propio organismo y lo que llevas por dentro? —solía despotricar mientras bebía la taza de café con tres cucharadas de azúcar que se hacía en la recámara durante la clase. Refulgía entonces en todo su esplendor el entramado de venas rojas de sus mejillas. Se balanceaba entonces el colgante que pendía de arrugado cuello –un elefante de coral que llevaba en su lomo un palanquín dorado en miniatura.

Sigue vagando por las calles del barrio, fisgoneando por los rincones, por las escaleras de los bloques de viviendas y en los cubos de basura, merodea por el patio del bloque de la calle Grzybowska, antes había allí un foso de arena para los niños, ahora es un aparcamiento. Sylwia del Gibalak, nunca llegó a conocerla. Ahora ya piensa en ella con frecuencia, cuando se aburre se imagina cómo podía ser. Allí, en el Gibalak, le contó un amigo que vivía en el mismo edificio, odiaban a los soplones. ¿Sabes lo que le hicieron a uno que era un chivato de la milicia? Le cortaron los pies. Con un cuchillo. Y luego ¿sabes qué más? Lo estrangularon con un alambre y se acabó. Su amigo se echó a reír y concluyó su relato metiendo la colilla en un agujero en el pavés de la escalera. Había ya un buen montoncito, podía pasarse el día admirando esa obra de arte.

Grzybowska y Waliców –en sus casas con puntales el tiempo bullía igual que el humo de la fábrica “Varsovin”, que envolvía el paisaje en una mugre de color pardo. Merodeando por esos mismos callejones se imaginaba a veces a esa Sylwia. Seguro que tenía las medias sucias y llevaba un feo gorro de lana. El pelo seboso porque en los barracones del Gibalak podían bañarse una vez a la semana, cuando calentaban el agua en un radiador de carbón, o incluso ni eso porque estaban todos beodos.

Nunca conoció a Sylwia, no la vio nunca, y sin embargo existía, vivía en algún lugar de este barrio que, aunque en apariencia estaba tan bien cuidado, con su biblioteca en la calle Chłodna, su iglesia con sus santos en las hornacinas y su dispensario clínico en la calle Waliców, tenía mucha podredumbre por dentro. Su olor se extendía sobre las rejas que camuflaban las ventanillas de los subsuelos, donde la gente echaba la basura. Seguramente lo que se pudría era un gato o una rata muerta.

Texto bajo el dibujo:

Idiota, ¿es que no te interesa saber cómo funciona tu propio organismo y lo que llevas por dentro?

Traduccion: Xavier Farré

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”