A female, contemporary ‘sanatorium novel’ drawing on The Magic Mountain

Off we go anyway. The suitcase trails behind me, like a sad dinosaur. The woman’s suitcase is so much smaller that I think, isn’t it normal, when you leave town in the autumn, to take wellies in case you go for a walk?

‘Are you here for long?’ she asks.

‘The whole month. That’s what my referral says. You?’

‘The same’.

So she’s not here for less time, so I’m a welly-clad slave to fashion, and one without a scrap of vision when it comes to steps on the return route. I’ll surprise her, I think.

‘The Social Security Office referred me. I had to. You understand. There was a committee and they said I had to come here for the whole month’.

‘It’s worse for the Socials’, she says. Her ‘expert’ mode kicks in. ‘First and foremost, we’ve no chance of getting a single. Even twin rooms are rare. Then there’s the trouble with the passes’. She looks at me, checking whether she’s made an impression. She has. She continues, ‘I’m a Social too this time, but I prefer to go private’.

I’m realising that she spends, so to speak, half her life here, that she’s now leading us at a confident pace, that we’ve turned left, her, me, our different sized suitcases, and we’re heading straight towards our destination.

‘You know where we’re going, don’t you?’ I ask.

‘Of course. I asked for directions because you have to break the ice somehow’. She stops, extends her hand. ‘I’m Beata. I thought, since you look younger than me, that you could be my friend. You’ll see, younger friends are very valuable here’.

I can’t escape, I think, I’ve got a big suitcase. I’m not supposed to run, I think. What the hell do I know, I think – she knows, and since she knows, shake her hand and introduce yourself nicely.

‘Kama’, I say. ‘From Warsaw’.

We’re walking again. Well, I’m walking behind her, because she’s walking. Behind me is the suitcase.

‘From Warsaw’, she says with a hint of disappointment. ‘That’s not the best. You know no one likes people from Warsaw?’

‘I know’, I say, because it’s hard not to know that if you’ve ever left the capital. ‘But I moved there for university and I just stayed’.

‘Ah, that’s a little better’, she says. But she doesn’t believe what she’s saying, it’s obvious. ‘I’m from Włocławek. It’s a good city. Anyway, no need to be ashamed of it’.

I’ve never been ashamed of a city, I think. How can you be ashamed of a city? What is shame for a city? We’re walking. We’ve made two more turns. The facility building is already looming on the horizon. I know, I’ve seen pictures of it online.

‘I’m a PE teacher’, says Beata. ‘Once, quite a long time ago, I won the junior vice championships in artistic gymnastics. Over the years it turned out that my bones didn’t much like that discipline. Which is why I’m hanging out here now. Though that’s not the only reason…’ She smiles suddenly. A kind of stretched-out smile. ‘Have you had your operation yet?’

Excerpt translated by Kate Webster

A female, contemporary ‘sanatorium novel’ drawing on The Magic Mountain

Translation rights: Grupa Wydawnicza Foksal, krystyna.kolakowska@gwfoksal.pl

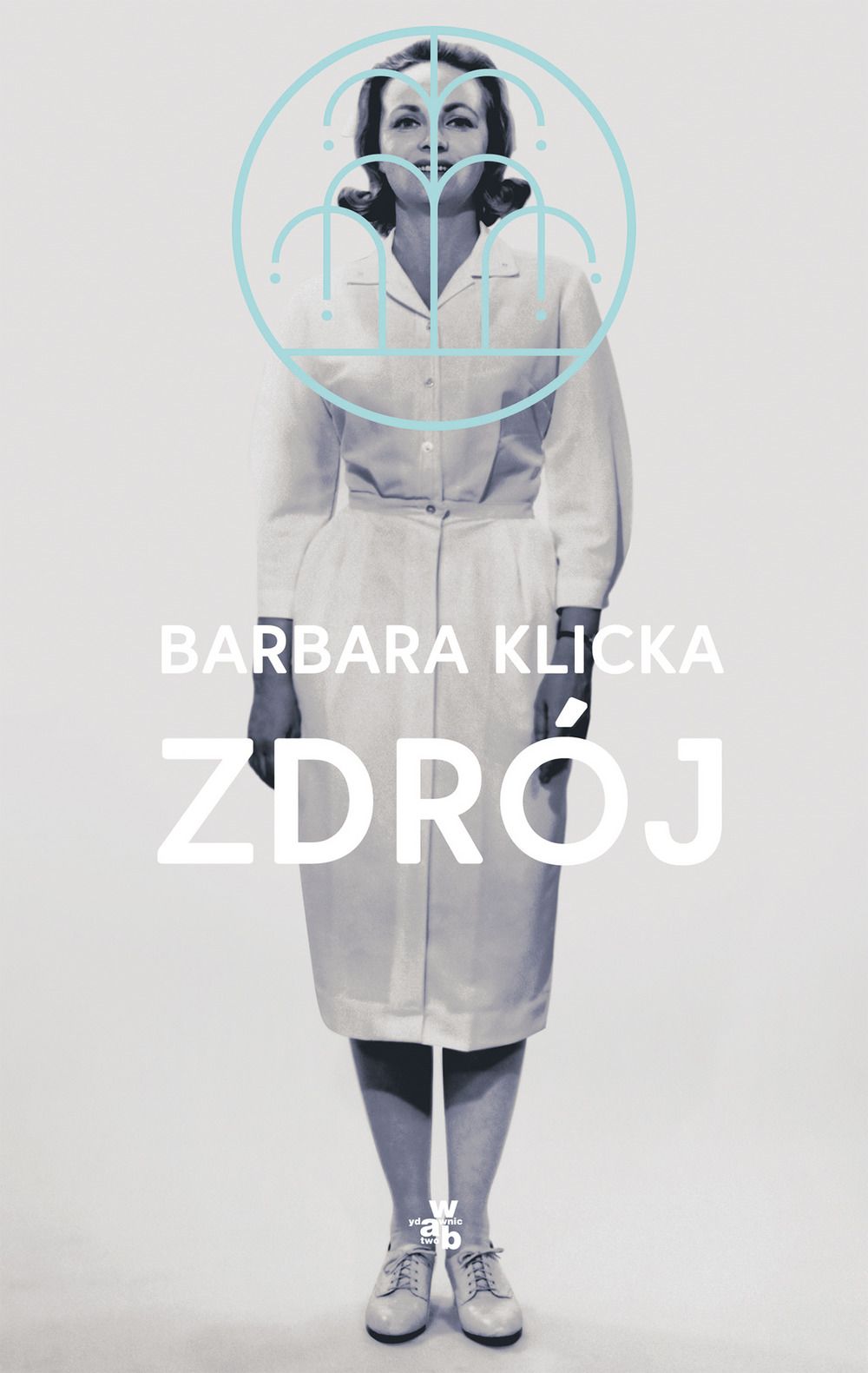

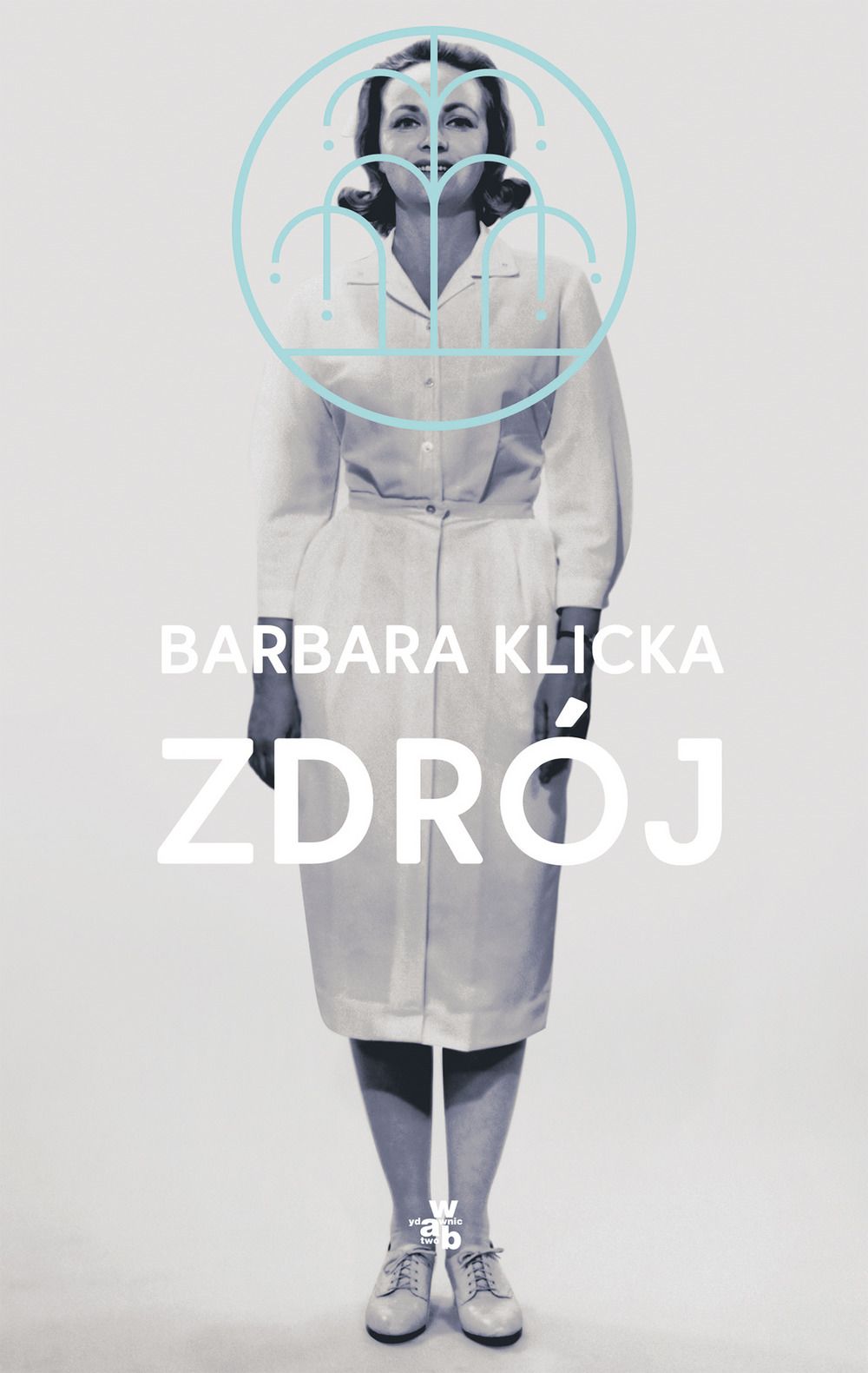

Zdrój [Sanitorium] is the debut novel by the recognised and award-winning poet Barbara Klicka. The work is written in a style typical of realistic prose – the author does not draw upon her poetic resources. Sanitorium could be called a ‘sanatorium novel’ and connections with this rich literary tradition, which stretches back at least to Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, are obvious. We have a heroine, Kama, who arrives from Warsaw for an extended rehabilitation holiday in Ciechocinek, a well-known spa town in the Kujawy region. Kama is thirty-three years old and has been ill since childhood – as a little girl she had often visited hospitals and sanatoria. This proves to be an important piece of information about her as the account of her weeks- long sojourn in Ciechocinek is punctuated by numerous flashbacks (most of them from when Kama was a twelve-year-old).

In her novel, the writer reveals something that could be called ‘sanatorium culture’. It shows how and what is talked about at a spa, what the typical behaviours of its inhabitants are, and how the medical staff carry themselves – something to which the author devotes the most space. This last aspect refers to what is perhaps the most interesting matter: attitudes towards the ailing body. Kama comes to the realisation that her doctors and physiotherapists have absolute power over her body, which is inevitably deprived of its intimacy whilst being subjected to various procedures. Some of the ways in which the staff behave can be regarded as inappropriate. We see, for example, those instances when Mariusz the masseur, in his desire to get closer to Kama, makes advances to her. In addition, there is another important male figure, Piotr the invalid, with whom the protagonist carries on fundamentally philosophical conversations about the meaning of life and suffering.

Although Sanitorium is a work of modest length, the writer has managed to weave many threads through it, often in just a few salient paragraphs. It is dominated by the poetics of abbreviation and understatement, and the narrative language is unusually concise, yet at the same time supple and precise.

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”