Translation rights: Ewa Bolińska-Gostkowska, bolinska@znak.com.pl

Design starts with education

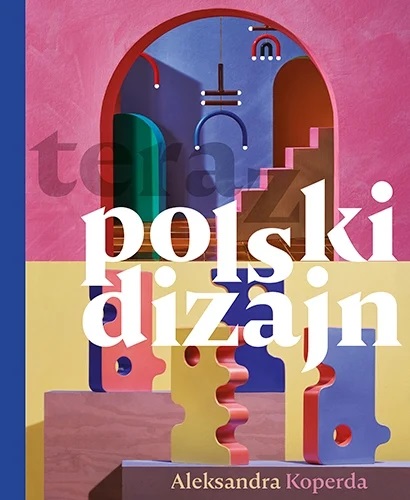

Polish Design Now is a guidebook to the past and future of Polish design. It’s not only a presentation of important figures in Polish design, people who have shaped the Polish applied arts environment since 1945, but is also a mine of knowledge about historical contexts as well as European and American design inspirations. Aleksandra Koperda introduces us to the philosophy of design, influential educational institutions, organisations of craftsmen and artists, factories manufacturing ceramic products.

First and foremost, what we will find here are interesting interviews with Polish designers of everyday objects. Koperda talks to, for example, Krystian Kowalski, Szymon Hanczar, Wojciech Mierzwa, Aleksandra Kujawska, Piotr Podziomek, Arkadiusz Szwed. Each of whom create very different designs – most often these are chairs, armchairs and tables, but also vases, porcelain sets, studio glass, jewellery. Equally different are their approaches to designing.

But that’s not all: Koperda asks founders of important brands about their industry experience. For example, she talks to Michał Woch, founder of Vzór, and Michał Szarko, founder of the Politura brand. Both of these brands introduce to the market historical designs which have never been mass-produced. A separate part of Koperda’s book is devoted to something she describes as “a different view”: when designs heavily gravitate towards art (as is the case of Bartosz Mucha’s works) or when the art of design does not materialise in any objects (Jo Jurga).

Anna Kałuża

Translated by Anna Błasiak

Aleksandra Koperda Polish Design Now

So how should we educate? On one hand, there is the design of everyday things, everything that we use has been designed, in a better or worse way. On the other hand, design transcended the borders of materiality a long time ago: we talk about designing services, experiences. On top of that, there is design which is located at the intersection of art and crafts, for collectors. When we talk of peoples of the North, the French or British, we can assume that they grew up in environments harmonious enough that a certain standard is an obvious thing for them. They have a basic sense of harmony, proportion, colour. I don’t know how much of it is conscious, how much is coded under the skin. I once wrote a piece about Jacob Holm’s interiors; he is the CEO of the Danish furniture brand, Fritz Hansen. I found an interview in which he had been asked whether it was true that he got his first Arne Jacobsen chair when he was eighteen. He confirmed and added, “But it wasn’t because I knew what good design was and I wanted to have a designer chair. I simply bought what I knew from home and from school. I knew it would be comfortable. And it was available. If I were Finnish, I would probably have bought an Alvar Aalto chair.” I realised then that in Poland things are completely different. There is no continuity. Good designs created in the Polish People’s Republic in most cases were never mass-produced, and if they were, they are not available anymore. People at that time didn’t think about whether they should buy a red sofa or choose a different colour. Instead they had to figure out where to get that sofa from in the first place. We have some catching up to do. I can see young generations already making conscious choices, of course within their budgets. They prefer to wait for something they have dreamt about, they are also inclined to take advantage of something that is not new – which nowadays is an important issue in design. Fixing, reclaiming, upcycling and the question of whether we should be still making new things. I think that yes, we should, but very responsibly. Designers must act for something and somebody. This requires very complex competences: humbleness, attention, curiosity, insight. A scientist’s discipline, an engineer’s precision and an artist’s sensitivity. Which is why design education must be interdisciplinary, and a designer should be a team player, since not many have an engineer, a scientist and an artist in them. Meanwhile investors still often think that “we must amaze the world, do something that nobody has done before!” It’s good to do that if we come up with designs that are smarter, simpler in use than those already created, but often it goes in the opposite direction. If something works, it doesn’t look good, if it looks good, it doesn’t work, and if it works and looks good, it will take 1000 years to break down. I also think that it’s not enough to educate designers. Everybody needs to be educated. Go back to basics. These days people often can’t tell the difference between different materials. If something looks like wood, then surely it is wood. People don’t know the difference between plywood and timber, between a laminated board and wood-effect paper. They don’t know how that affects the production, the price, the durability. It’s the same with clothes, with everything we buy. Where does milk come from? From a fridge. Where does cotton come from? From a shop. How can people make conscious choices and appreciate responsible design if they don’t know these things?

Translated by Anna Błasiak

***

Aleksandra Koperda, La hora del diseño polaco

Entonces, ¿cómo deberíamos educar? Por un lado, tenemos el diseño de las cosas cotidianas: todo lo que usamos ha sido diseñado, de mejor o peor manera. Por otro lado, el diseño hace tiempo que traspasó las fronteras de la materialidad: nos referimos al diseño de servicios, de experiencias. Está, además, el diseño en el cruce entre el arte y la artesanía, el diseño de coleccionismo. Cuando hablamos sobre los pueblos del norte, los franceses o los ingleses, podría afirmarse que se han desarrollado en un entorno tan armonioso que un determinado estándar es para ellos algo natural. Tienen un sentido básico de la armonía, la proporción, los colores. No sé cuánto de esto es consciente y cuánto está codificado subcutáneamente. Una vez escribí un texto sobre la casa de Jacob Holm, director ejecutivo de la empresa de diseño de muebles Fritz Hansen. Encontré una entrevista en la que, a la pregunta de si era cierto que la primera silla que había comprado, con dieciocho años, era de Arne Jacobsen, lo confirmó y añadió: «Pero no porque tuviera claro qué es el buen diseño y quisiera tener una silla de diseño. Había empezado la universidad y necesitaba una silla, así que me compré la que conocía de casa y de la escuela. Sabía que era cómoda y, además, era asequible. Si hubiera sido finlandés, seguramente habría comprado una silla de Alvar Aalto». Me di cuenta de que en Polonia la cuestión es muy distinta. No hay continuidad. La mayoría de los buenos diseños que se crearon durante la etapa comunista no se llevaron a producción y, si lo hicieron, ya no están disponibles. Por aquel entonces, la gente no se planteaba si comprar un sofá rojo o de otro color, sino dónde encontrar un sofá. Tenemos que ponernos al día. Observo que las generaciones jóvenes empiezan a elegir de forma consciente, dentro del presupuesto disponible, claro está. Pero prefieren esperar a tener algo con lo que han soñado, y también están dispuestas a utilizar objetos usados, lo cual constituye un planteamiento fundamental para el diseño actual. Reparar, recuperar, reciclar, y preguntarse si deberíamos seguir fabricando cosas nuevas. Pienso que sí, pero con mucha responsabilidad. Los diseñadores tienen que trabajar por algo y para alguien. Eso exige unas competencias muy complejas: humildad, atención, curiosidad, perspicacia. La disciplina de un científico, el perfeccionismo de un ingeniero y la sensibilidad de un artista. La formación en diseño debe, por tanto, ser interdisciplinar, y el diseñador debe trabajar en equipo, dado que pocas personas reúnen al mismo tiempo las características del ingeniero, el investigador y el artista. Aun así, muchos inversores siguen pensando que «debemos sorprender al mundo, hacer lo que nadie ha hecho». Está bien si creamos proyectos más inteligentes y fáciles de usar que los que ya existen, pero a menudo sucede lo contrario. Si algo funciona, no es bonito; y si es bonito, no funciona; y si es bonito y funciona, se desintegrará dentro de mil años. También creo que no basta con educar a los diseñadores. Hay que educar a todo el mundo, volver a las bases. Hoy lo habitual es que la gente no sepa diferenciar los materiales. Si algo parece de madera, seguro que es de madera. No distinguen entre contrachapado y madera aserrada, o tablero laminado con papel con apariencia de madera. No saben cómo esa diferencia influye en la producción, el precio, la durabilidad. Ocurre lo mismo con la ropa, con todo lo que compramos. ¿De dónde sale la leche? Del frigorífico. ¿De dónde sale el algodón? De las tiendas. ¿Cómo esperar que la gente escoja de forma consciente y aprecie el diseño responsable si no sabe nada de esto?

Traducción: Teresa Benítez Rodríguez

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”