Holewiński makes human sexuality the key to the epoch he describes

Konstantin Andrievich Yurin was forty-one and all he dreamed about was his bed and peace and quiet. Especially on a day like to- day, with his head exploding into a million

pieces after yesterday’s drinking session at the rooms of Lieutenant Rex, Commissioner of District no. 4 – Bielany.

He heard a knock at the door and a moment later saw Klachkin’s huge head. Yurin looked up at him.

“Gavrotsky has arrived,” he reported. “Shall I let him in?”

For a long while he had to think who the intruder was. He evoked the face of the nark, his piercing blue eyes. And his hands. Some machine had half cut off two of the fingers on his left hand. After years of work, he so- metimes observed in astonishment that there was an apparatus installed in his head, which after pushing a button, brought to mind the faces of criminals, agents, lovers, the people he had sent to penal servitude and the ones who had refused him loans. In short – everybody.

Yurin didn’t have the strength to talk to him.

“Says it’s important,” Klachkin said, not giving up, although no doubt after serving Yurin for six years and three months he must have known that the captain’s stubborn efforts to focus on a single point was eviden- ce of his intense experience the night before.

“Let him wait,” he waved a hand and before the door had closed had reached out for a carafe standing on the left-hand side of the desk. He picked it up and lo- oked at it but decided not to pour any water from it into a glass standing on a wooden coaster.

He ought to go to a doctor, request leave, get out of Warsaw, that was certain. But instead, he spent eve- ry day in his office. District no. 7 was his curse … If they would only post him somewhere else. And ideally send him back to Russia, to Piter. To Alyosha, his childhood friend, who had done very well for himself and was a rich man. They had seen each barely a year before. Alyosha had laughed at his uniform and of- fered him a position in one of his numerous haulage companies. Yurin had turned it down then, although Nastasiya Philipovna took a deep breath at the thought she might be returning to her mother.

He didn’t like the city or its inhabitants. He didn’t like them nor understand them. He spoke Polish – without an accent, he believed. But so what? The women were attractive there, his flat comfortable, he enjoyed the local alcohol, but the fact that the newly appointed Governor-General of Warsaw, Constantin Claudie- vich Maximovich, kept having to flee to the fortress in Zegrze in fear of his life didn’t fill him with optimism. There had been attempts on the general’s life, they might also try to assassinate an ordinary captain. Why not? They were able to shoot at Captain Rastagayev on Żelazna St.? How lucky he’d been, it had seemed. The bullet passed through his neck and into his chin, where it had lodged. He’d been discharged barely two months ago from the Hospital of the Infant Jesus, and a week later it turned out he had a nervous collapse. They’ll shoot at me sooner or later, thought Yurin.

Thoughts about the gallows were often hatching in Konstantin Andrievich’s head. For what else did tho- se bastards deserve? They wanted to kill, kill and kill again. He didn’t understand those new-fangled efforts, those socialists, “going to the people”, education for all, and those bombs which, let’s face it, killed completely random passers-by and children. Neither did he understand showing those murderers mercy. He cared for order, he was its guardian, because that was the way things were, because somebody had to take on that lousy responsibility. Shoot, shoot at them like in January? Did a hundred die? A thousand could for all he was concerned. Whoever got in the way of bul- lets deserved them.

Excerpt translated by David French

Holewiński makes human sexuality the key to the epoch he describes

Translation rights: Zysk i S-ka, anna.giryn@zysk.com.pl

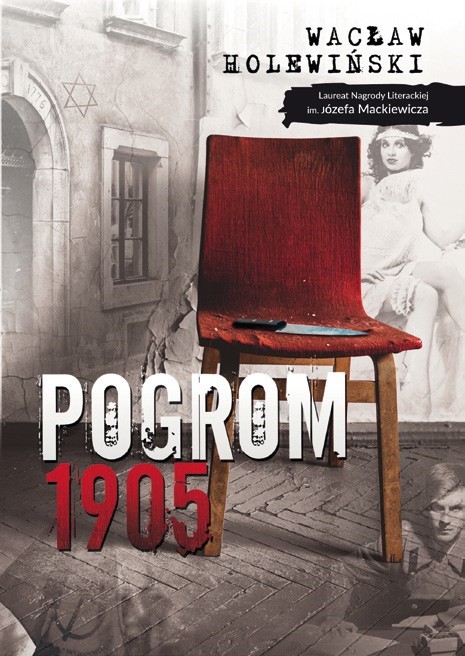

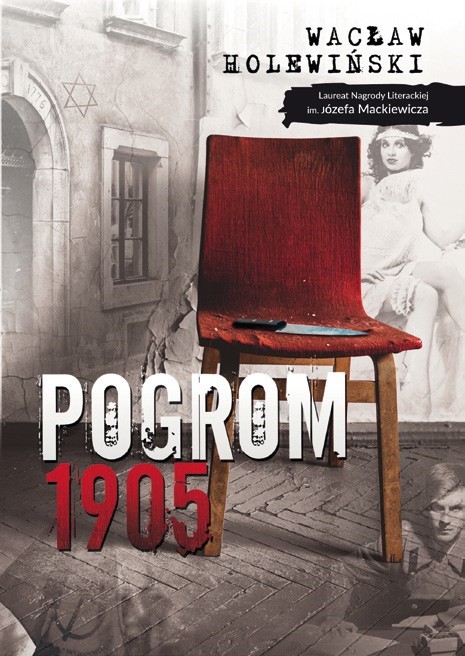

In the fascinating historical novel by Wacław Holewiński, several dozen figures of different social status are thrown together by fate during the authentic street tumult that led to the lynching of several pimps and prostitutes in Warsaw in 1905. Was it a spontaneous pogrom caused by anti-Semitic sentiments? Was it carried out by Jews in their own community? Or maybe it was a Russian provocation inspired by the tsarist service?

Many characters stand for a collective hero, but this is only part of the truth, because the most important hero of Pogrom 1905 is the Warsaw of the beginning of the 20th century – a vibrant metropolis of extremes. Modern, and at the same time dirty and repulsive. Disgustingly rich and frighteningly poor. Frivolous and at the same time spiritual. Diverse but also full of class-ethnic tensions between Poles, the Jewish minority, and the elites of the Russian invader. Not necessarily the “Paris of the North”, but rather a rapidly modernising Moloch, controlled only nominally by the Russians, because in fact chaos rules.

Historical novelists often search for new perspectives to tell about the past in a refreshing way. They choose as heroes criminals, outcasts, the excluded, and all kinds of “others” that the great narratives have hitherto ignored. In turn, Wacław Holewiński makes human sexuality the key to the epoch he describes. He portrays women prostituting themselves, teenagers forced to sell their bodies, men overwhelmed by lust – both lustful youths and old lechers, and even a doctor specialising in venereal diseases. Everything in Pogrom 1905 revolves around carnality, but the writer does not reach for it like a pornographer. He does not want to arouse excitement, but rather has the ambition of telling the story in a new, bold, and broad- minded way.

Marcin Kube, translated by Katarzyna Popowicz

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”