The life of an individual enmeshed in history

‘He started an acrimonious quarrel with a waiter, who on noticing that we were foreigners, decided that he could treat us with contempt,’ recalled Andrzej Bernhardt. ‘Mirek Chojecki invited us to dinner at Brasserie Lipp. We left a lot of food on the plates, so my uncle asked the waiter to wrap up the leftovers the way it was done in America. With a scornful expression, the man threw everything into one bag, so uncle demanded three separate ones – one for the French fries, one for the meat, and one for the salad. The furious waiter finally complied, but he also overcharged us on the bill! This was not, as it may seem, a minor pub squabble. He simply would not let one thing go, he would not let anything pass. He was so sensitive, so thin skinned, that it seemed he had almost no skin at all.’ (…)

His publishing arrangements in France were going badly; finally during his last stay in Paris, he published a volume with Fayard. He did not have a place in the French book market. He was known in Germany, America, Sweden, he received prizes, including in Israel, where he went while already very ill. He did not count on the Nobel Prize, he knew that political correctness reigned and there was no chance for him at all. Would he have even accepted it – alongside Gorbachev? Being in the society of laureates was very important to him. He was chronically short of money, especially since he did not like to ask anyone for it. He bought a lot of books, and not only literature, but, for example, histories of objects – the hammer, the carpenter’s plane, the wristwatch; lives of ants and apes; a history of ancient Egypt. He bought maps, graphics, stamps. He collected crystals, rocks, that always stood on his orderly desk. He loved beautiful objects – and peace and quiet. As time went on, his contacts with people became more and more difficult. They made him more and more upset, distracted, but especially Poles – who were not punctual, unreliable. (…) He received fewer and fewer telephone calls, though sometimes it happened that some people got lucky, and managed to make contact. He did not respond to letters, especially from young poets who sent him their poems for comment. He thought this was embarrassing. One should judge one’s own work.

(…) He did not want to be an emigrant, he always travelled on the so-called temporary stay, but as he turned sixty, he insured himself and paid premiums. This was fortunate because it was then that his illnesses began. His relations with hospitals and doctors grew worse. He could not find a physician who would satisfy him, he demanded too much. He wanted not only to get good treatment, but that the doctor should be intelligent, well-read, know and understand things. He left the house less and less, and finally stopped going out at all. He went to the bookshops on Saint Germain by taxi, because his home was far from the metro. He no longer took advantage of being in Paris, in France, and there was no point in staying there, paying rent, a large sum on which he could live in Poland. He returned home in 1992 and we still corresponded. He asked for books that he most needed in Poland. Recently, he was interested in ancient Egypt, and wanted catalogues from exhibitions on this subject. Although I did not want him to, he always sent money, writing that he was going to kick the bucket shortly and wanted to settle all his accounts.

Excerpt translated by Peter Obst

The life of an individual enmeshed in history

Translation rights: Wydawnictwo Fronda, redaktor@wydawnictwofronda.pl

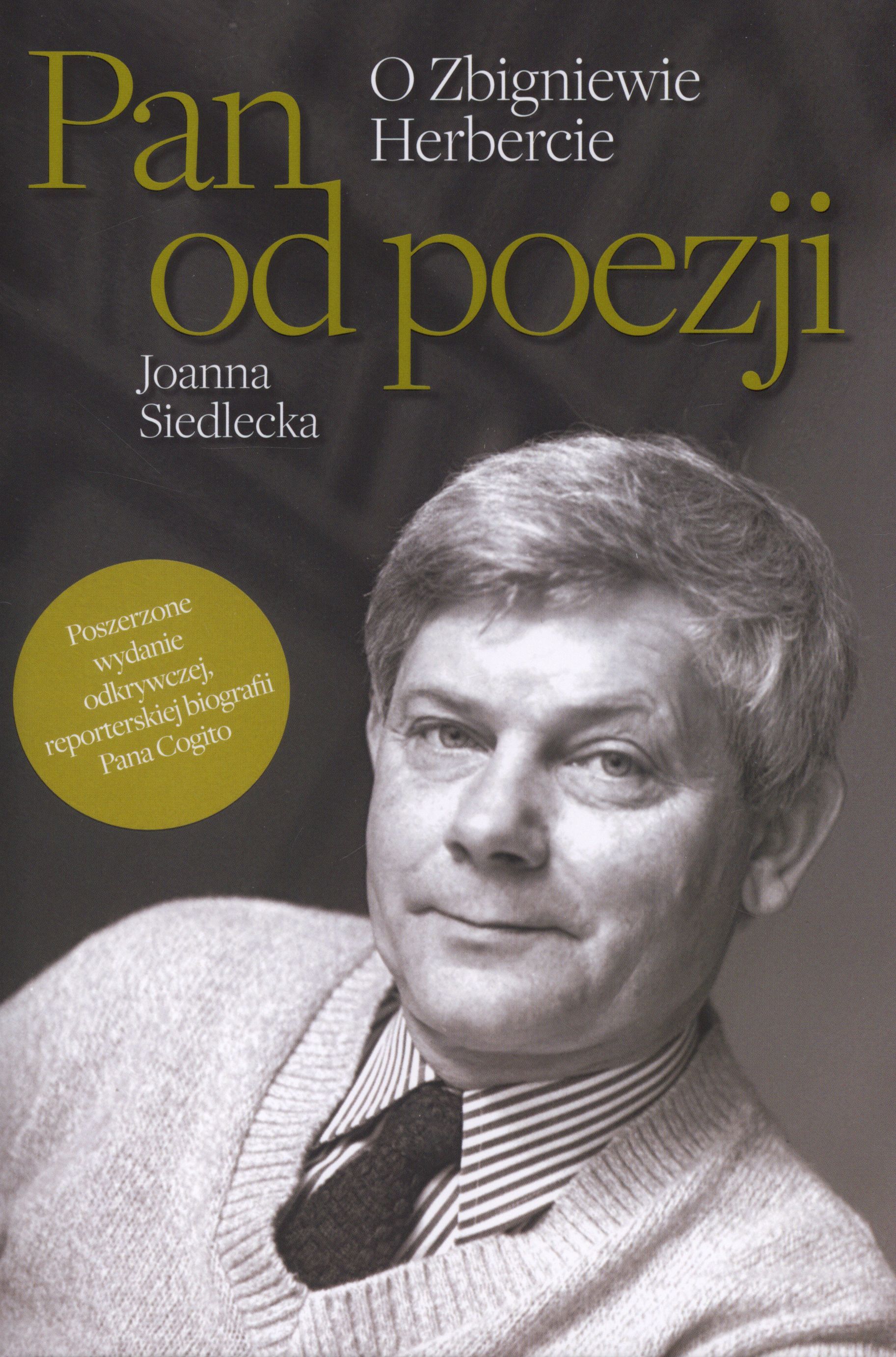

This book, a biography of Zbigniew Herbert, one of the greatest Polish poets of the twentieth century, examines the background of his life from the earliest years to the last, and also offers posthumous opinions about the poet who near the end of his life expressed some uncompromising political views, polarising the Polish intellectual environment during an intense time of political change.

Joanna Siedlecka, a reporter and journalist with a keen detective sense, has uncovered numerous pieces of evidence documenting previously unknown facts in the biography of Herbert. The poet began his career with the volume String of Light (1956). This placed him on the map of Polish poetry as a classicist, while his most recent poems, including those published in the volume Epilogue of a Storm (1998), strongly influenced both the post-thaw development of Polish poetry and the formation of an uncompromising stance in opposition to the governing regime. The author, who has published books that expose the infiltration of Communist influence into the literary milieu (Declassified Biography, Case Name ‘Lyricist’), as well as biographies of controversial writers (The Ugly Black Bird, Mahatma Witkac), illuminates both the personal aspects of Herbert’s complicated life, as well as his attempts to find a place for himself within the realities of People’s Poland. It also depicts the divergence between Herbert’s actual private life, and the legend of the poet as a hero and an ‘unbreakable prince’ that he shaped himself and which grew within the milieu of the opposition. The book is enriched with numerous illustrations, copies of documents, letters and photos from various periods of his life. It is written in a lively, clear, and accessible language, a pleasant read not only for literary scholars, but also for the general public. Its undoubted value, but also a quality of Siedlecka’s writing, is to show the life of an individual enmeshed in history, in the life of society. In this instance, the reader – through Herbert’s personal history – is introduced not only to the realities of a socialist country, but also to the complicated history of the fall of Communism in Poland during the early nineties.

Marzena Woźniak-Łabieniec, translated by Peter Obst

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”