Poles should go back to defining themselves along the North-South axis

Does some secret map of Europe exist? A map that, if we could decipher it, would lead us along the hidden paths of our con- tinent, overgrown with the passage of time?

Would it tell us who we are? Or, who we cannot be? When Europe is spoken of today, our attention is primarily focused upon the unification of the continent. We mainly occupy ourselves with the extent to which our continent forms a unity, whether, and under what conditions, unity can be established . . . This political and intellectual compulsion towards unity, which cannot be denied for certain practical reasons, but which draws its power from a fear of divisions, has effectively killed contemporary Europe’s capacity to perceive and understand differences, and along with that the potential for critical self-understanding and an under- standing of the complex character of our own identity . . . This is why contemporary Europe has become politically and intellectually boring and barren, and some will go so far as comparing it to an infirm old woman. Meanwhile, from the perspective of knowledge, divisions and differences are more interesting and constitute for culture the other, more significant, side of the problem of Europeanness.

The dividing lines running across the continent deter- mine our present consciousness. They are the foundations for differing behaviors and differing ways of perceiving the world. They arrange themselves into a kind of secret map of Europe. For the inhabitants of Central-Eastern Europe, the main division that im- poses itself as the most obvious and important is the division into East and West . . . Besides the division into East and West there is also a much deeper division, much more significant for European identity, for understanding what Europe is and how it came to be, and, at the same time, key to understanding Polishness and its unbreakable ties with the process of the formation of European culture. It is the division between North and South. Our Europe was born from the collision of the North with the South and this division through the ages has marked out the spiritual, cultural, and political development of the Old Conti- nent. The demarcation line between the North and South coincides, more or less, geographically with the line of the Rhine and the Danube, that is, the historical border to which the world of the ancient civilization of Christianized Romanitas reached politically. This border, at various historical intervals, divided or joined the continent, its northern and southern part, starting from very distant times – from Arminius, the German prince of the Cherusci, who in the Teutoberg Forest destroyed 20,000 of Varus’s legionnaires, to Charlemagne, who was the king of the Franks, but became the first emperor of a reborn Latin Western Europe, to subsequent German emperors, attempting to gain leadership over the world of the West as a new Rome. The division into North and South can be seen later in many key European historical events . . . Even today’s crisis of the project of European integration, the European Union, once again reveals to us the vitality of this immemorial division of the continent, since the main line of the Euro Zone runs between the countries of the North and South.

Where is Poland situated in this division? Precisely right in the middle of it.

Excerpt from the essay The Secret Map of Europe, translated by Artur Rosman

Poles should go back to defining themselves along the North-South axis

Translation rights: Marek A. Cichocki, mcichocki@natolin.edu.pl

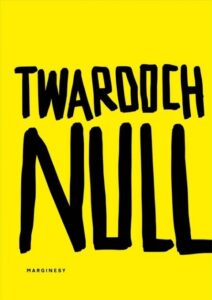

Where does Poland lie? For two centuries the Poles were suspended between the East and the West. Accession to the European Union finally seemed to settle where we belong. The problem is that the West we aspired to is now falling apart. Professor Marek Cichocki, philosopher, political scientist, and former adviser to Lech Kaczyński, argues in this brilliant book that Poles should give up on thinking in terms of East-West categories and go back to defining themselves along the North-South axis. Poland is a Slavic country with a Roman form.

Cichocki masterfully shows how from the very beginning Polish culture drew from classical sources. The powerful Commonwealth of Two Nations was directly based upon republican models from ancient Rome. Polish struggles with 20th-century totalitarianisms were essentially a defense of this classical heritage against modern barbarism. The ultimate confirmation of this tie with Rome was the pontificate of the Polish Pope, John Paul II. And so today, instead of looking towards foreign capitals, Poles should cultivate at home their own ancient, republican, and Catholic form. In this way, even when they distance themselves from the post-Enlightenment liberal discourse that dominates in today’s EU structures, they will always remain Europeans. The real Europe is the result of the joining of North and South, the adoption by the pagan Gauls, Germans, and Slavs of classical and Christian heritage.

As Cichocki argues evocatively, this project is endangered not only by Eastern barbarianism, manifesting itself in Russian communism, but also Western liberal universalism. “Poland will be Latin, or it will not be at all,” he concludes. The same can be said about Europe.

Paweł Rojek, translated by Artur Rosman

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”