Vivid and powerful picture of the communist regime in Albania – by an acclaimed young reportage writer who gives a voice to the ones who had been denied their own

The Eighth Circle: Shadows

Today, the people who tortured me are shadows in my head. I met one of them on the street once, during a demonstration.

‘Fatos!’ he cried. ‘Do you recognise me? It’s me, Gjergj!’

Of course I recognised him, because he was the guard whose kicks were particularly brutal, a ruthless man. Now he was supporting us in the protests against the government of Sali Berisha. One day I’d like to sit down opposite the people who tortured me and ask them: “Who were you then? Were you people?’ But I know they’re not capable of reflection. Only a few of them really understand what they did to others. The rest see themselves simply as tools in the hands of the system, and that’s why they don’t feel any responsibility for their actions.

I also once met one of the three judges who sentenced me the second time, and who in 1979 sentenced three of my friends to death: Fadila Kokomani, Vangjela Lezhe and Xhelala Koprenck. On my way into a café, I stopped to let an elderly man go ahead of me, but he also stopped to let me through, and then he looked me in the face and asked: “Do you recognise me, sir? Can we get a coffee?’

And then I realised who was there in front of me. We sat down at a table.

That man had determined my fate and that of my friends. Perhaps you’re wondering why I didn’t hit him in the face? I think I just wanted to understand him. But I couldn’t look at him. I just sat there and listened to his voice.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I signed those sentences condemning you… I signed them and I know it was wrong. But did I have a choice? I’d have ended up in prison, just like you. Do you remember when Vangjel Lezho asked for some spectacles, to read out his defence, and I gave him my own?’

I looked him in the eyes, as I had many years ago. When you have charges hanging over you and you enter the court room, you immediately scrutinize the judges’ faces, you look for any trace of goodness, empathy, a modicum of humanity, you look for hope for yourself. It occurred to me then that he might not have been as bad a man as I’d thought.

‘Did you realise the accusations were fabricated?’ I asked. ‘Did you really believe it was all true?’

‘No… I mean, it was obvious… We knew the accusations were fabricated.’

They knew. So they could have said, ‘No, I won’t sign this death sentence.’ They could have said, ‘I love the party, I love the laws it passes, but I will not consent to falsehood.’ But they didn’t say that. They signed it all.

Now when I think about it… How free were they? Is your consciousness free? They were all like children whose lives lay in the hands of the adults, in the hands of the party. They couldn’t grow up, they couldn’t be free. In some ways that excuses them… But in those days everyone took certain decisions. Everyone had a margin of freedom, everyone had a choice. Those who determined the lives of others could have behaved dishonourably or correctly too.

While I was in prison, I sometimes wondered why my father didn’t do anything to help me – he was an influential Communist, after all. Why did no one in Hoxha’s entourage oppose the regular purges? Nobody ever stopped him from doing anything. Nobody ever stood up to him.

Excerpt translated by Zosia Krasodomska-Jones

Extended English sample and book report available (anna.rucinska@nurnberg.pl)

Vivid and powerful picture of the communist regime in Albania – by an acclaimed young reportage writer who gives a voice to the ones who had been denied their own

Translation rights: Andrew Nurnberg Associates Warsaw, anna.rucinska@nurnberg.pl

Foreign language translations: Spain, Italy; an excerpt was also published in Granta Magazine.

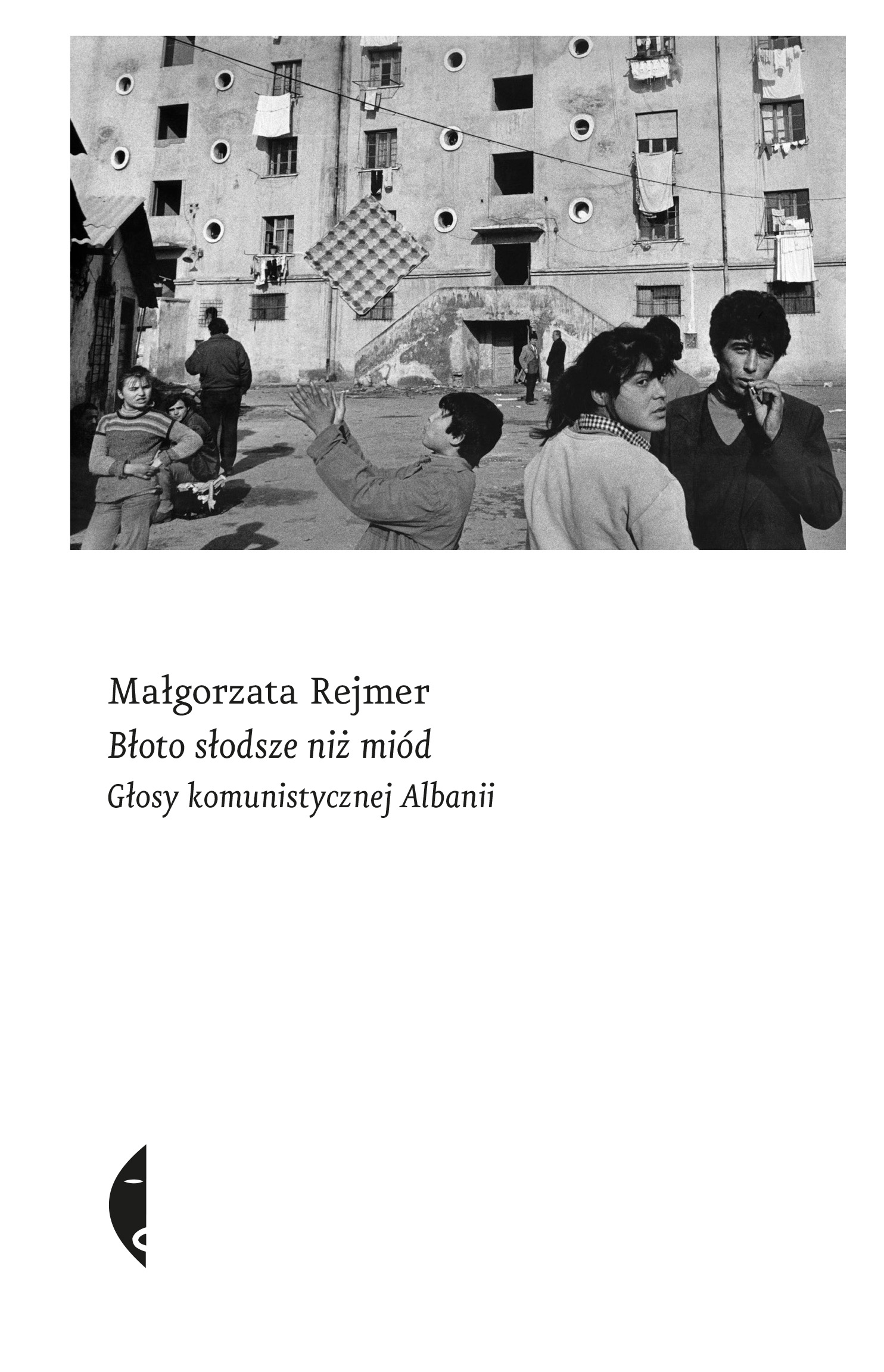

Albanian communist Enver Hoxha made a Utopia in his country – he took everything from his people and forced them to live from one moment to the next; he deprived them of their property and their God. However, none of this brought them happiness; on the contrary, it drove them into bondage, fear, and misery.

Almost thirty years after the fall of the communist dictatorship, Małgorzata Rejmer interviewed those Albanians who managed to survive. This was no simple matter. Their country had undergone a criminal Utopian experiment with which Poles are intimately familiar, except that they experienced it for only ten years, while the Albanians endured it for forty-six. To render a picture of this system, the author talked to writers, artists, and simple folk, patiently listening to their tales of how Communism drove their homeland back to the times of indenture, making them a ‘reserve of browbeaten animals.’

We should recall that, in the latter half of the progressive twentieth century, one-third of the countries in Europe were groaning under communist régimes. Among these, the Albanian régime was the worst. This is a book about a penal system and the incomprehensible cult of a good and faultless leader; about the willpower of an oppressed nation to endure suffering; about their will to live, and the triumph of opportunism which helped them survive the nightmare of hunger, humiliation, and torture. It is also about the dignity, which many Albanians refused to surrender. This book is spare and simple in form, but it runs deep.

Now that no one shoots at people attempting to flee the Albanian Gulag, the depleted country is trying to find its feet once more. This will not be easy. There has been no reckoning with the past: none of the parties responsible for the crimes of the Hoxha era have been brought to justice, and the new system, as well, is founded on lies. There is no one to forgive, for the guilty have vanished. In effect, one half of Albanian society continues, in childlike fashion, to believe in the myth of a righteous, though mismanaged Utopia, while the reflections of the more conscious citizens stop in midstream. Everything is coated in mud. One reads this book with a powerless sense of rage that Communism – the most despicable evil that the world has ever seen – has never been brought to justice, and never will be, not in Albania or anywhere else.

Grzegorz Filip, translated by Soren Gauger

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”