Translation rights: Magdalena Kosińska, magdalena.kosinska@agora.pl

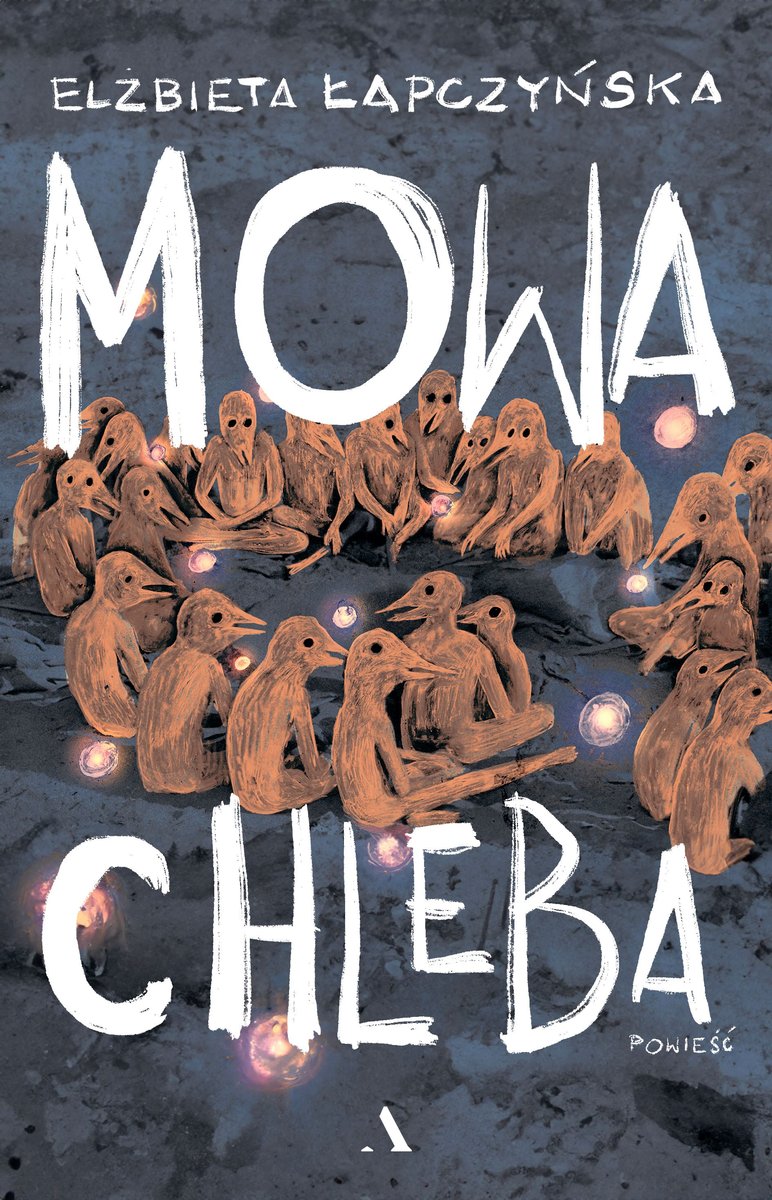

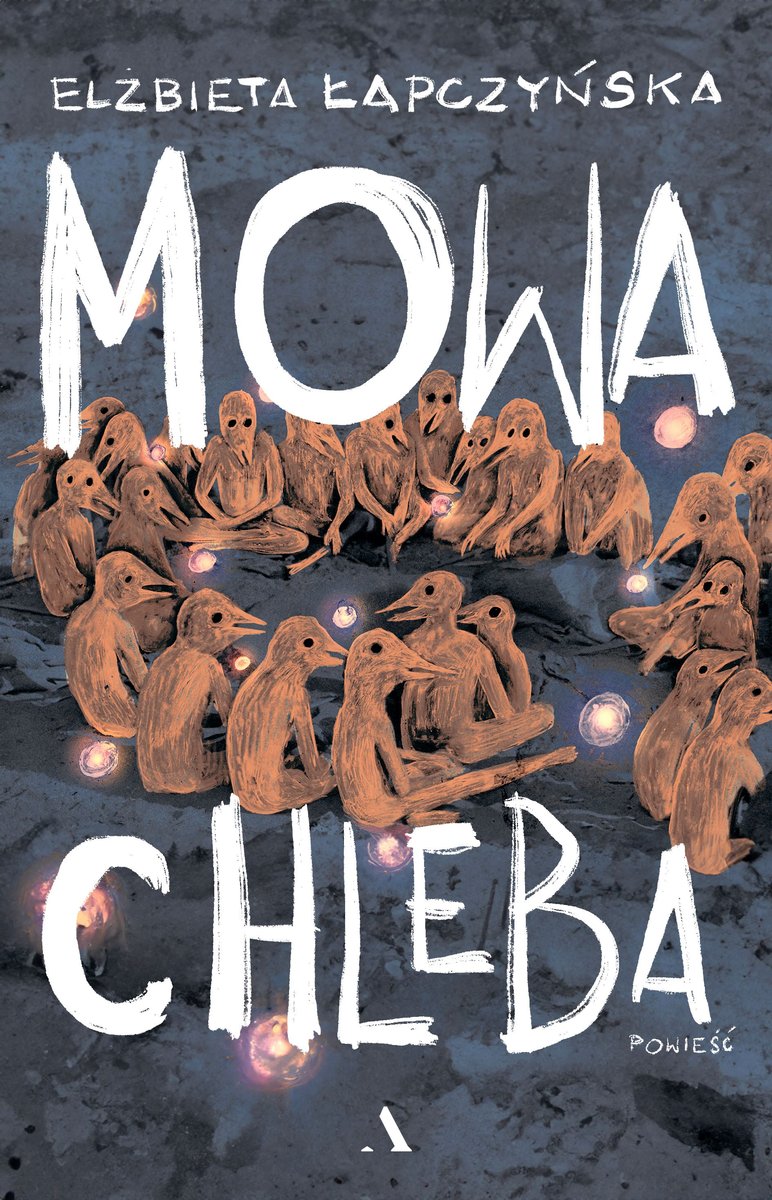

The hell of patriarchal biopolitics

This novel takes place in Crăiești, a Transylvanian village whose former barracks have been transformed into an orphanage. The facility is staffed by village women who come down the road every day and cross a moat to reach the nest of evil, as they describe it. To avoid being infected with evil, they must never make eye contact with the orphans, its permanent residents. Children here are fed on pig’s milk and human blood, and no one crosses the gates of the orphanage except the employees. The book revolves around the women’s lot and daily struggles – with work, with their bodies and the bodies of others. Their portrayal gives us a complete image of the grim determinism of a world where the divide between the enclave of evil and normalised everyday village life turns out to be false, a fact skilfully problematised by the author. Life outside the facility is a real-life fantasy of collectivist social engineering: authoritarian Romania in the 1980s, where the fundamental task was to prop up the birth rate, and as a result orphanages were opened on a mass scale. Here there are no easy differences of landscape, nor unambiguous and rapidly judged characters who might demand a reader’s empathy. Suspending the dictates of realism, Łapczyńska disturbs our stereotype of children, women and animals as victims of male perpetrators. In this book, each person experiences and commits some form of violence, fundamentally borne by bodies that are exploited based on the situation, but in keeping with how society categorises them.

Katarzyna Trzeciak

Translated by Sean Gaspar Bye

Elżbieta Łapczyńska, Bread Speech

The sun had just risen in Crăiești, though no one noticed. In early summer, the morning caught you by surprise. Most of the village women were busy nursing, some with two breasts at once. They’d feed, starting with the youngest, the weakest. Sometimes not only their own, but neighbours’ too. Mouths sucked impatiently.

At this time of day, older women milked the pigs. The piglets had to wait, humans got fed first. In this place they drank pig’s milk. Each sow had to give birth much more often than anywhere else, seven or eight times in her life, thirteen piglets or more each time. Even so, milk ran short. While all the women were busy nursing, the birds raced along, shrieking in flight.

Lenuța was putting on her shoes sitting down; she couldn’t bend over because two of her sons were still nursing. The eldest was waiting his turn, but not the fourth – he refused, squeezing into a dark corner.

“Get over here,” she snapped like a horsewhip, “ain’t gonna be nothing else.” But he jumped away and flew out the door. Thump-thump-thump along the stoop and the grass swallowed him up. He ran. Lenuța didn’t have to look out the window to know. First down onto the road, then he’d climb up to the hill. When he fled the first time, she ran after him. She burst into the pigsty, the door bouncing off the boards. Using her gaze and her shoe, she squeezed through the pigs. Where you at?, she shouted. Her son was lying in a hole. He’d lain down amid the piglets at the sow’s teats. He was sinking into pink skin, he’d almost forced his head through the folds to the inside of the body, he and the other piglets were floating in a fluid belly, thick as caramel, the same juices circulating between his and the piglets’ stomachs.

In the yellow-painted room, it was now day. Colours, bright and juicy, fell over the houses and grass. Lenuța, running far too late, sloppily tied a scarf over her head, tucked her bleached bangs under it and set off on her bike to work. The other mothers were clearly able to get their teats back under their work clothes in time. Her mouth clutching a smoke she lit on the bike, Lenuța rode off toward the bellowing of beaks. The birds were shrieking crazily as they followed a new shipment to the facility.

There was chaos outside the blue building, quick movements, uncertain gestures. Crying at different in-breaths, but grating similarly on the ear. Women like Lenuța – from Crăiești and surrounding villages, in white aprons – were going back and forth between the truck and the door. Their hurry drove away the recent dawn. They would jump off the truck bed either with a bundle throwing its arms upwards, or with an unbundled who used its own feet. The birds fell silent, observing the commotion from the branches of birch trees. Crăiești Orphanage was receiving new arrivals.

Some of the women would disappear into the main corridor, others would go down the stairs to the basement. Lenuța left her bike by the blue wall and ran up to the truck. Another woman placed a baby in her arms. Warm and flabby.

“Minus one,” rumbled Mr. Buni, jostling Lenuța with a box of papers. He didn’t look at her. She didn’t look at him. Or at the baby.

It had lots of long, curly hair, thick eyebrows, squinty eyes and a head in a gesture of refusal. Just like her son who ran away to the pigs. Its gaze seemed grownup. Lenuța went down the stairs.

Orange spots reflected on the floor of the dark corridor from the light escaping through semi-opened doors. If she put an empty can to her ear and flicked it with her finger, she’d hear a sound like the one that quivered between the walls.

Translated by Sean Gaspar Bye

***

Łapczyńska Elżbieta, El discurso del pan

En Crăiești el sol acababa de salir, aunque nadie se diera cuenta. El precoz verano sorprendía por la mañana. La mayoría de las mujeres de la aldea estaban ocupadas amamantando, algunas con ambos pechos a la vez. Alimentaban por orden, empezando por los más pequeños, los más débiles. A veces no sólo amamantaban a los suyos, sino también a los del vecino. Sus bocas mamaban con impaciencia.

A esa hora las mujeres mayores ordeñaban la manada. Los lechones esperaban: el hombre tenía que comer primero. Aquí se bebía leche de cerdo. Se esperaba que cada cerda pariera, a diferencia de cualquier otro lugar (siete u ocho veces en la vida), mucho más: trece veces o más. De todos modos, la leche escaseaba. Cuando todas estaban ocupadas amamantando, los pájaros gritaban impacientemente.

Lenuța se calzaba sentada, sin poder agacharse porque aún estaba dando el pecho a dos de sus hijos. El mayor esperaba su turno. El cuarto no, se negaba, metido en un rincón oscuro.

—Ven aquí, no habrá otra cosa que ésto —le espetó ella como un latigazo, y él dio un respingo y salió pitando por la puerta. Unos saltos por el porche y lo absorbió la vegetación. Se escapó. Lenuța no tuvo que mirar por la ventana para saberlo. Primero corre hacia la carretera, luego subirá a la colina. Cuando huyó por primera vez, ella corrió tras él. Entró en la pocilga con tanto ímpetu que la puerta golpeó las tablas de la pared. Con la mirada, metiendo las botas entre cerdos, lo buscaba. ¿Dónde estás? El hijo estaba abajo. Tumbado entre los lechones, pegado a los pezones de las cerdas. Se sumergía en la piel rosada, surcaba con la cabeza los pliegues hacia el interior del cuerpo, junto con los lechones se elevaba y en esta barriga líquida, espesa como el caramelo, los mismos jugos fluían entre su estómago y los de los lechones.

En la habitación pintada de amarillo ya estaba amaneciendo. Los colores, brillantes y jugosos, caían sobre las casas y el césped. Lenuța, que ya llegaba muy tarde, se ató el pañuelo a la cabeza de aquella manera, metió bajo el borde su flequillo rubio oxigenado y salió en bicicleta hacia el trabajo. Al parecer, otras madres sabían tapar a tiempo sus pezones con la ropa de trabajo. Con un pitillo en la boca ya encendido y subida en la bicicleta, Lenuța se dirigió hacia el lugar de donde provenía el chillido de muchos picos. Las aves escoltaban el nuevo transporte a la fábrica con alaridos de locura.

Delante del edificio azul había alboroto, movimientos rápidos, gestos inseguros. Llantos en diferentes registros, pero que atacaban los oídos de manera parecida. Mujeres con delantales blancos como Lenuța, que vinieron de Crăiești y pueblos de alrededor, iban y venían rápidas entre el camión y la puerta. Con las prisas espantaban el reciente amanecer. Saltaban de la caja del camión o con fardos desde los que se estiraban los bracitos infantiles hacia el cielo, o con bultos más grandes, que se valían de sus propias piernas. Los pájaros se callaron, observando la algarabía desde las ramas de los abedules. El orfanato Crăiești recibía a los recién entregados.

Algunas de las mujeres desaparecieron en el pasillo principal, otras bajaron las escaleras hacia el subterráneo. Lenuța apoyó su bicicleta contra la pared azul y corrió hacia el camión. Otra mujer le pasó un bebé. Tibio y blando.

— Menos uno —tronó el señor Buni, rozando a Lenuța con una caja de papeles. Él no la miraba. Ella no le miraba. Tampoco al niño.

El pequeño tenía mucho pelo largo y rizado, cejas espesas, los ojos entrecerrados y la cabeza en gesto de negación. Igual que su hijo, él huía hacia los cerdos. Miraba como si de pronto se hiciera mayor. Lenuța bajó las escaleras.

En el suelo del oscuro pasillo se reflejaban manchas anaranjadas: era la luz que se escapaba por la puerta entreabierta. Si uno acercaba una lata vacía al oído y la hacía sonar con el dedo, oiría una reverberación similar a la que temblaba entre las paredes.

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”