Everyone has to eat, including dictators

We lived poorly, but I can’t remember us ever going hungry. We usually ate manioc, or manioc flour with a vegetable of some kind. Meat was an extreme rarity. My father always had two or three cows, but if he did slaughter one of them, all the meat went to the market. We needed the money to pay our debts; we always owed our neighbours for something. The food eaten by the Luo, the tribe I am from, is quite like the food of the mzungu, the white people. The main ingredients are cooked vegetables or meat. The mzungu eat potatoes; we eat manioc, buckwheat, or rice. Except that it’s not enough for the mzungu to have a little buckwheat or manioc, and a small piece of meat; the mzungu have to bake cheese too, put it on their vegetables, and stew the meat in wine first. Mzungu cuisine is the food of people who want to show that they have power. Because food is power. I learned that from cooking for presidents. If you have food, you also have women, you have money, you have people’s admiration. You can have whatever you want. Our food is the food of people who know what hunger is. We have nothing to prove to anyone. We eat to have the strength to go on working.

While I was living with my parents, I had various occupations. First I dabbled in music; I played the orutu, a kind of fiddle that’s popular among people from the Luo tribe. It has one string, and you play it with a bow, resting the instrument against your hip. I used to earn money playing it at weddings and other special events.

Then my uncle took me out on his boat to be a fisherman. I sailed with him for about two years.

Until one day a hippopotamus attacked our boat. We saw it from afar, swimming toward us. An angry hippo is much worse than a crocodile: it moves very fast in the water. It swam up and overturned our boat, sending us all flying helplessly in different directions. It’s a miracle no harm came to anyone that day, because that hippo had already killed several people, and all the fishermen around the lake were afraid of it. After the hippo attack I said to my uncle, ‘I wasn’t the only one of fourteen siblings to survive just to die now if it comes back.’

My uncle agreed with me. One of his sons, Sylvester, was working in Kampala, Uganda, at a club that was popular with the mzungu. My uncle said I should take the boat to Kampala and find the club, and his son would be sure to help me to find a job.

For us, the Luo, family ties are very important. Did you know that the former American president Barack Obama is Luo too? His father comes from a village twelve miles from here. And even though he has never lived here, Obama often helps his family in any way he can. So I knew that Sylvester would not refuse to help me.

I boarded the boat from Kisumu to Entebbe, and as soon as it docked, I went straight to my cousin.

The “Kampala” club was a very important place for the mzungu, because most of the people sent by the British government to work in Uganda spent their first few weeks living in the hotel next to it, until a suitable rental home was found for them. My cousin was a groundskeeper there and swept the floors. He was very pleased to see me and went straight to the manager and instantly got me a job as a waiter’s assistant. I didn’t know a word of English, but luckily it wasn’t necessary. All I had to do was smile and carry food from the kitchen to the dining room.

What about the hippopotamus, you ask? One day it simply disappeared. People say it must have been the spirit of a warrior who had come to take revenge on his enemies.

Excerpt translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Everyone has to eat, including dictators

Translation rights: Andrew Nurnberg Associates, anna.rucinska@nurnberg.pl

Foreign language translations: Czech Republic, France, Holland, Italy, Russia, Slovakia, USA, Ukraine (Jak nakarmić dyktatora) Szabłowski’s other works have been published in Estonia, Finland, Germany, and Spain as well.

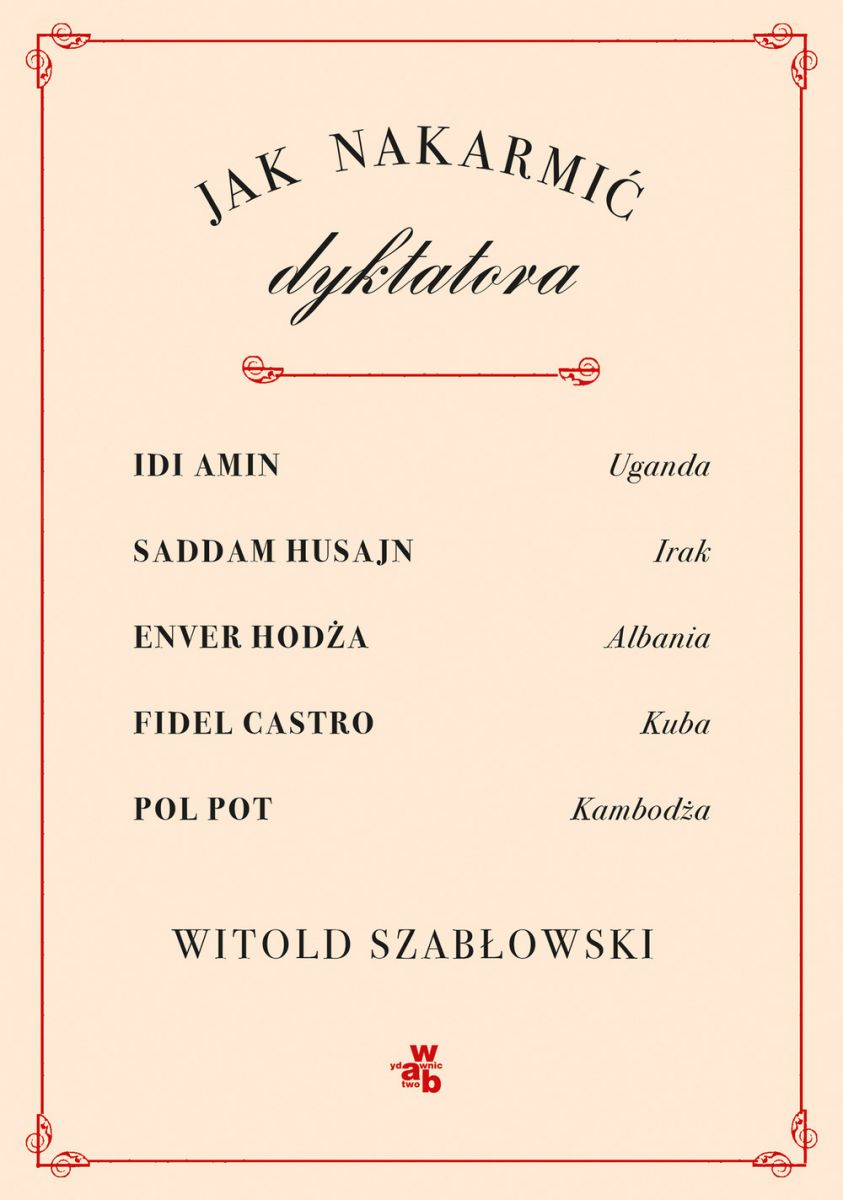

The idea behind How To Feed A Dictator is simple, but that’s exactly where its strength lies. There’s a Polish idiom that translates literally as “to get to know something from the kitchen”, which means showing some aspect of life from the unfamiliar, unofficial side. And it’s quite literally from the kitchen that Witold Szabłowski has chosen to present some of the world’s greatest evildoers. Everyone has to eat, including dictators. And so the people who cooked for them had to be highly trusted, and under constant surveillance.

Szabłowski spent several years trying to get in touch with the chefs who worked for Idi Amin, Fidel Castro, Pol Pot, Saddam Hussein and Enver Hoxha. Most of them keep a low profile. The Cuban who cooked for Fidel Castro is the only one to boast about it publicly. He gives interviews to the Western media, runs a restaurant in central Havana and is a local celebrity, which was probably only possible because in the past he had been a comrade-in-arms of Castro and had done his bit for the revolution. But he became a cook rather by accident.

Each of these stories is different, but they’re all fascinating. The woman who cooked for Pol Pot, the Cambodian dictator – the worst mass-murderer since Adolf Hitler, responsible for the death of two million people – talks about him with genuine love and devotion. She still believes he did a great deal of good for the country. Idi Amin’s cook has answered the question of whether the Ugandan dictator was a cannibal thousands of times. His story is incredible in that he survived, despite having also cooked for the country’s previous president.

But the most shocking story of all concerns the man who cooked for Enver Hoxha, the Albanian dictator. For more than a decade the poor man had to take part in daily self-criticism sessions. Anyone who did this unconvincingly might not survive. On top of that, he had to break all his ties with the outside world, apart from the most essential. One time, when he accidentally ran into an acquaintance in the street and exchanged a few words with him, the other man ended up in the security service’s dungeons.

In fact, How To Feed A Dictator is a tale about terror – the terror of murderers who are afraid for their lives, and the terror of those whose lives are at the mercy of their whims.

Mariusz Cieślik Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”