The fictional Rokitnica is a closed microcosm, to which strangers are not allowed

The captain made his way along this section of the track. Amidst the brush on the right, there was a flash of reflected sunlight from a piece of metal. Witczak shielded his eyes. At

the bottom of the embankment stood a cross, adorned with a wreath of fresh flowers. Swearing like a sailor, the captain slid down the slope, pulled his shirt sleeve over his hand, and carefully parted the nettles. At first, he thought that the cross was erected after the murder, but no – the rusted metal was decidedly old-looking. And under the fresh wreath was a second one, withered with age. Witczak called to Hanka.

“What’s this cross?” he asked, as the girl struggled toward him through the brush.

“I don’t know,” she replied, disconcerted. “I’m not from here. I spent my vacations here with my aunt, and I know a lot of people from Rokitnica, but no one ever said anything to me about a cross. Probably some accident with a train or something like that.”

“And these flowers?”

“Maybe someone wanted to memorialize that girl?” “The murder victim? Fine. And these? He lifted the fresh flowers to reveal the flowers underneath – withered, brown, and so shrunken that it was impossible to identify what kind they were. “How long, in your opinion, would they have to hang here to look like this?”

“I don’t know,” she answered, increasingly uncertain. “A few days? Longer?”

“Longer,” she acknowledged. “Two weeks, maybe.” “Which means someone hung flowers on this cross a week before the murder. That doesn’t seem strange to you?”

“Not especially,” she said, but the captain wasn’t listening to her.

He dropped the wreath and clambered back up the embankment. The girl followed in his footsteps. They reached the top just in time to see a man in rubber boots making his way through the meadow. Witczak watched him carefully, registering his dark hair, close set eyes, and hooked nose. Despite his rubber boots, dirty shirt, and pants smeared with who knows what, the man was handsome in an unsettling way that must appeal to women.

“Franciszek Chojniak?” the captain asked his companion.

“Yes.”

“He lives here with his family?”

“With his wife. They don’t have children. Ewa had an accident and now she’s paralyzed.”

Chojniak untied the cow from its post, patted her side, and began to lead her in the direction of the house. He didn’t even glance at Hanka or Witczak.

“I want to see him tomorrow at the police station,” the captain said. “Send him a summons.”

“If we send it by mail, it’ll take three days to arrive.” “Well, then notify him some other way,” Witczak’s irritation was returning.

The girl hesitated for perhaps half a second and then ran back down the embankment, shouting, “Franek, wait!” The captain closed his eyes in despair.

Excerpt translated by Megan Thomas

The fictional Rokitnica is a closed microcosm, to which strangers are not allowed

Translation rights: Andrew Nurnberg Associates Warsaw, anna.rucinska@nurnberg.pl

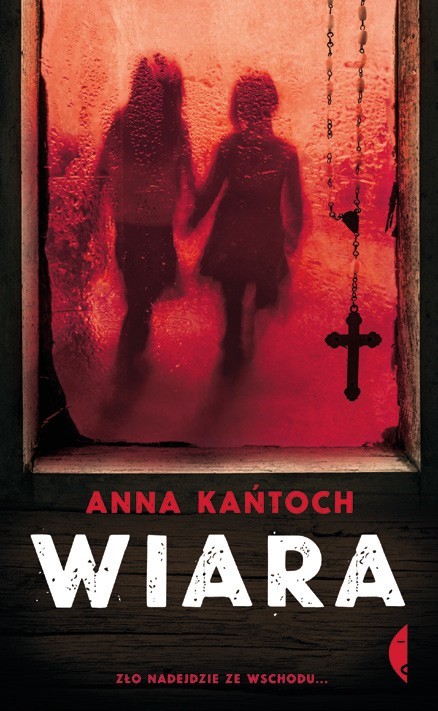

Although Anna Kańtoch is known primarily as the author of excellent short stories and fantasy novels (she is a five-time winner of the Janusz Zajdel Prize, the most prestigious award in Polish fantasy), in just two years she has become a leading author of crime fiction. This is significant, as the competition in this genre is exceptionally tough.

Her criminal debut, Mercy, was well received by critics and readers, but it is Faith that shows the full potential of this writer. The strength of her prose is not about a remarkable main character, since Captain Witczak “was a very average man” with “a nondescript” face; it is also difficult to regard as such the young priest who discovers a young woman’s body and for this reason becomes an important participant in events. Neither is it about some interesting reality (the action takes place in the 80s at a summer resort, close to a nuclear power plant that is being built), which, moreover, confirms that the Polish provinces today have the most to offer to culture – foreign included.

What impresses most is the author’s excellent ear for language, especially as regards dialogue full of dialects, the skilful use of detail (this is why the stifling atmosphere of Faith is so overwhelming), and above all intrigue: intricate and dark, based rather on the craft of writing and the idea than on a rushing plot and the stacking up of corpses. The fictional Rokitnica is a closed microcosm, to which strangers are not allowed. This applies both to the parish priest, who tries to learn something about the mysterious disappearances of his predecessors, as well as to Witczak, unsuccessfully trying to persuade the locals to share their secrets. The author’s fantasy background allows her to create a climate of strangeness: it is difficult to separate reality from what is imagined and even paranormal.

Kańtoch touches on topics that are scarcely present in Polish literature: beside the faithfully recreated small-town landscape of mid-1980s Silesia, the writer brings the reader closer to the conflict between the clergy and militia, recalls Polish hippies, and recreates the customs and aspirations of Poles at that time. If it is true that a crime story portrays society today more faithfully than a literature of manners, then Faith would be its best example.

Krzysztof Cieślik, translated by Katarzyna Popowicz

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”