Translation rights: Zofia Dimitrijević, zofia.dimitrijevic@czarne.com.pl

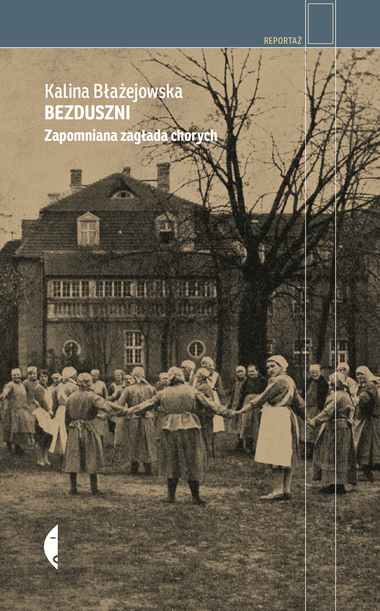

A harrowing reportage about the fate of psychiatric hospital patients and the inmates of care homes during

World War II

The subject of World War II might appear to have been thoroughly exhausted in the literature. However, writers and researchers continue to arise who deepen our knowledge and uncover further shocking facts concerning this period.

The author has turned her attention to the most overlooked group among the victims of World War II – children and adults in psychiatric clinics and care homes.

According to the author’s estimates, at least 20,000 patients from psychiatric hospitals and inmates of care homes died during the war. The exact number of victims from this group is impossible to establish due to incomplete, destroyed or lost documentation. The tragic stories of the sick are overlaid with the concepts of eugenics and euthanasia, in which those who could produce offspring with hereditary conditions were deprived of life. The victims were often subjected to medical experimentation and, years after the war, many of the doctors who took part in it have still not been held accountable for their crimes.

This book constitutes a thorough piece of reportage. The author has not only accessed archival sources in the form of acts, minutes of hearings and newspaper articles, but has also discovered witnesses who, though few, preserve the memory of events of more than eighty years ago. Soulless Beings sheds new light on a recently discovered, but still not fully understood history.

Katarzyna Wójcik

Translated by Anna Zaranko

Kalina Błażejowska, Soulless Beings: The Forgotten Extermination of the Sick

The modern therapy that parents had been promised does not exist. Unless that is what you would call the bed-wetting treatment practised at the Loben Jugendpsychiatrische Klinik. Some children end up there precisely for this reason. Like Henryk Lelonek from Katowice, for example, who was admitted in spring 1943. He was five years old when, following his father’s arrest, he was taken away from his mother and placed in a national-socialist youth centre (NS Jugendheimstätte) in Bielsk, where they tried to make him into a model German. After sixteen months, however, the centre’s management concluded that he was “incapable of remaining at the youth home as he wets the bed”. They decided what should be done with Henryk amongst themselves: that is, the main social welfare office of the Upper Silesian NSDAP, the district social welfare department, the Katowice office for youth affairs, and the office of the mayor of the city of Katowice. The boy would surely have been surprised to learn just how important he was to the Reich.

Doctor Hecker bases her original method of “treating” children like him on the premise that incontinence is most often the result of a lack of will power. And if the will proves difficult to train, some kind of external restraint should be introduced. Specifically: withholding food and drink from four in the afternoon until morning. In this way, Hecker maintains, even children struggling with this problem for years are cured within a few days.

The true task of unit A is not treatment, however, but discipline, diagnosis and segregation. Hecker and her subordinates are to evaluate if a “useless” child can become a useful adult. Are they “sufficiently adept, from a physical point of view, to live and earn a living beyond the institution, working for below market remuneration”, or are they “completely unfit for life within society”.

This was the task approved by the Upper Silesian office for youth affairs. After a clinic visitation in December 1942, the directors of the Jugendamt conclude that “the establishment of the Loben Jugendpsychiatrische Klinik constitutes a decisive step in the education of productive youth”, since it promised “to ascertain clearly which children deserve support and to be raised in homes and families, and which should be excluded from society”. […]

Children generally spend six to eight weeks in Unit A. Sometimes shorter, sometimes longer. During this time, they are measured and weighed, their lungs are listened to, their throats and ears inspected, tests are carried out for dysentery and syphilis, and injections are given. Knees are tapped and feet agitated with a reflex hammer, light is shone into pupils. Older pupils are also tested for intelligence. Basically: knowledge of German and the German early years school curriculum. Poles and Silesians stand no chance of good results. Perhaps they know “where the sun rises” or “what is mercy”, but they do not understand the questions. And even if they guess, they reply in their own language. In other words, badly.

The nurses and doctors observe the patients constantly: how they speak, how they move, play, eat and sleep. They do not overlook any deviation from the norm – and they consider the norm to be unconditional obedience, a complete lack of sexual drive, absolute control of the emotions and physiological needs. Polish and German children are evaluated with equal strictness.

Translated by Anna Zaranko

***

Kalina Błażejowska, Desalmados. El genocidio olvidado de los enfermo mentales

La terapia moderna prometida a los padres no existe. A no ser que se llame así al tratamiento de la incontinencia urinaria que se practica en la Jugendpsychiatrische Klinik Loben. Algunos niños acaban allí sólo por este motivo. Como Henryk (Henio) Lelonek, un niño de siete años de Katowice, ingresado en la primavera de 1943. Tenía cinco años cuando, tras la detención de su padre, fue alejado de su madre e internado en el Hogar de las Juventudes Nacionalsocialistas (NS Jugendheimstätte) de Bielsko, donde intentaron convertirlo en un alemán ejemplar. Sin embargo, al cabo de dieciséis meses, la dirección del centro consideró que «no era apto para permanecer en el hogar juvenil porque mojaba la ropa de cama». La oficina principal de ayuda social del distrito NSDAP de Alta Silesia, la oficina de ayuda social de la comarca, la oficina de juventud de Katowice y la oficina del alcalde de Katowice deliberaron qué hacer con Henio. El muchacho se habría sorprendido al saber que era tan importante para el Reich.

El método original del Dr. Hecker para «tratar» a niños como Henio se basa en la suposición de que, la mayoría de las veces, la incontinencia se debe a una falta de fuerza de voluntad. Y si resulta difícil ejercitar la fuerza de voluntad, hay que introducir restricciones externas. Concretamente: no darles de comer ni beber desde las cuatro de la tarde hasta la mañana del día siguiente. De este modo, afirma Hecker, incluso los niños que llevan años con este problema se curan en pocos días.

Sin embargo, el verdadero cometido del pabellón A no es tratar, sino disciplinar, diagnosticar y segregar. Hecker y sus subordinadas deben evaluar si un niño «inútil» puede convertirse en un adulto útil; si es «físicamente lo bastante capaz para vivir y ganarse el sustento fuera de la institución, trabajando por un salario inferior al del mercado», o «no es apto para vivir en la sociedad en absoluto».

Se trata de una tarea aprobada por la Oficina de Juventud de Alta Silesia. Tras una visita a la clínica en diciembre de 1942, los directores del Jugendamt evaluarán que «la creación de la Jugendpsychiatrische Klinik Loben constituye un paso decisivo en la formación de jóvenes productivos», dado que permitirá «determinar con claridad qué niños merecen apoyo y serán criados en hogares y familias, y cuáles deberían ser excluidos de la sociedad» […].

Los niños suelen pasar entre seis y ocho semanas en el pabellón A. A veces menos, a veces más. Durante este tiempo, se les mide y pesa, se les ausculta los pulmones, se les examina la garganta y los oídos, se les hacen pruebas de disentería y sífilis, se les administran vacunas. Se les golpean las rodillas y los pies con un martillo neurológico y se les ilumina las pupilas con una linterna. En los mayores se examina la inteligencia o, en realidad, sus conocimientos de alemán y del programa de los primeros cursos de las escuelas alemanas. Los polacos y los silesianos no tienen ninguna posibilidad de obtener un buen resultado. Puede que sepan «por dónde sale el sol» o «qué es la piedad», pero no entienden la pregunta. E incluso si la adivinan, responden en su propio idioma. Es decir, mal.

Las enfermeras y los médicos observan constantemente a los pacientes: cómo se expresan, se mueven, juegan, comen y duermen. No pasan por alto ninguna desviación de la norma, considerando como norma la obediencia absoluta, la falta total de deseo sexual, el control estricto de las emociones y las necesidades fisiológicas. Juzgan con la misma severidad a los niños polacos y alemanes.

Traducción: Elżbieta Bortkiewicz

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”