Full-blooded novel with a generous helping of 20th-century history of Silesia

I raise my face toward the late-autumn, post-war sky. I am twenty-seven and I feel ancient. I’ve been through a great deal. I am twenty-seven years old, five foot nine, I am thin, my uniform hangs on me

like a sack pulled in at the waist. I am clean shaven, though I haven’t been to the barber in a long time; my salt-and-pepper hair is ruffled and old blood still makes it clump into unpleasant tufts, and I have lice, too. I try to put on my officer’s cap, it barely fits over the bandage on my head, so I remove the bandage and feel the back of my head growing damp; a little blood continues to seep from my still-unhealed wound, making my hair stick together even more. It’s nothing. It’s nothing.

On the corner of Wrangelstrasse stands an old, moustachioed veteran, with no right arm and no insignia on his grey uniform. At the front, the regiment numbers sewn on to epaulettes have long since been covered by grey sheaths, but this man has completely unstitched his epaulettes, along with the stripes on his collar. On his cap, instead of the imperial black, white, and red cockade, he has pinned on a red ribbon, as if someone had shot him through his forehead. Like me, he has no coat – I can see he must be as cold as I am, and I am very cold. I approach and greet him, but he only snaps something in response, though he can see perfectly well I’m in an officer’s uniform. I should be surprised, but I’m not. Hanging from his one remaining forearm is a ring of the cheapest sausages, which contain practically no pig’s meat, but which still look mouth-watering; I’d gladly buy a few, I’m hungry, but I remember that I literally haven’t got a pfennig in my pocket. Nothing. I remember how back in 1917, when I was on my final leave in Berlin and when the scar left by the continental blockade on our economy was both terrible and visible to the common people, even in those days traders would set out street stalls with sausages. I remember one young man in particular who stood not far from the hotel I was staying in, on Friedrichstrasse. He was as strongly built as a militia grenadier, he wore a bowler hat, a monocle, and a little waxed and black-dyed moustache curled straight up, with a white apron over his dark clothes and a tin pot marked “Wurst” hanging around his neck and resting on his belly, and from this pot he sold steamed sausages, less fatty than before the war and much more expensive, but he sold them, and I could afford them and I bought one every time I went past; I’d stand next to him and eat, much happier at being able to buy a frank than at the frank itself, which tasted awful.

Now I can’t even afford the cold, ersatz franks this one- armed veteran is selling, I can’t afford anything.

I haven’t been this poor since I started earning money tutoring during my last year of prep school. I learned well the value of money, every mark, every pfennig, I know how hard my papa and little brothers worked for their pay. And I always wanted more. More money, more of what I could buy with it. I didn’t want to save every pfennig, conserve matches by snapping them in two, smoke the cheapest tobacco, I didn’t want to do everything my father did because he had to.

Excerpt translated by Sean Gasper Bye

Full-blooded novel with a generous helping of 20th-century history of Silesia

Translation rights: Wydawnictwo Literackie, j.dabrowska@wydawnictwoliterackie.pl

Foreign language translations: Twardoch’s works have been published in Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Macedonia, Netherlands, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine, and USA. Rights to Humbel have been sold to Germany (Rowohlt) and Netherlands (Nieuw Amsterdam).

Literature needs stars. Today, Szczepan Twardoch is without doubt a star of Polish literature. He’s a writer whose work has been adapted for screen (a serialised version of his King of Warsaw will soon premiere on TV) and is translated more and more often into the most important world languages (including German and English), a writer whose readers can’t wait for his books and whose public pronouncements arouse emotions – a rare feat for contemporary prose writers. But despite the contemporary cult of celebrity, you can’t become a star of literature without knowing how to write. And Twardoch can write – proof of which is his new book Humbel.

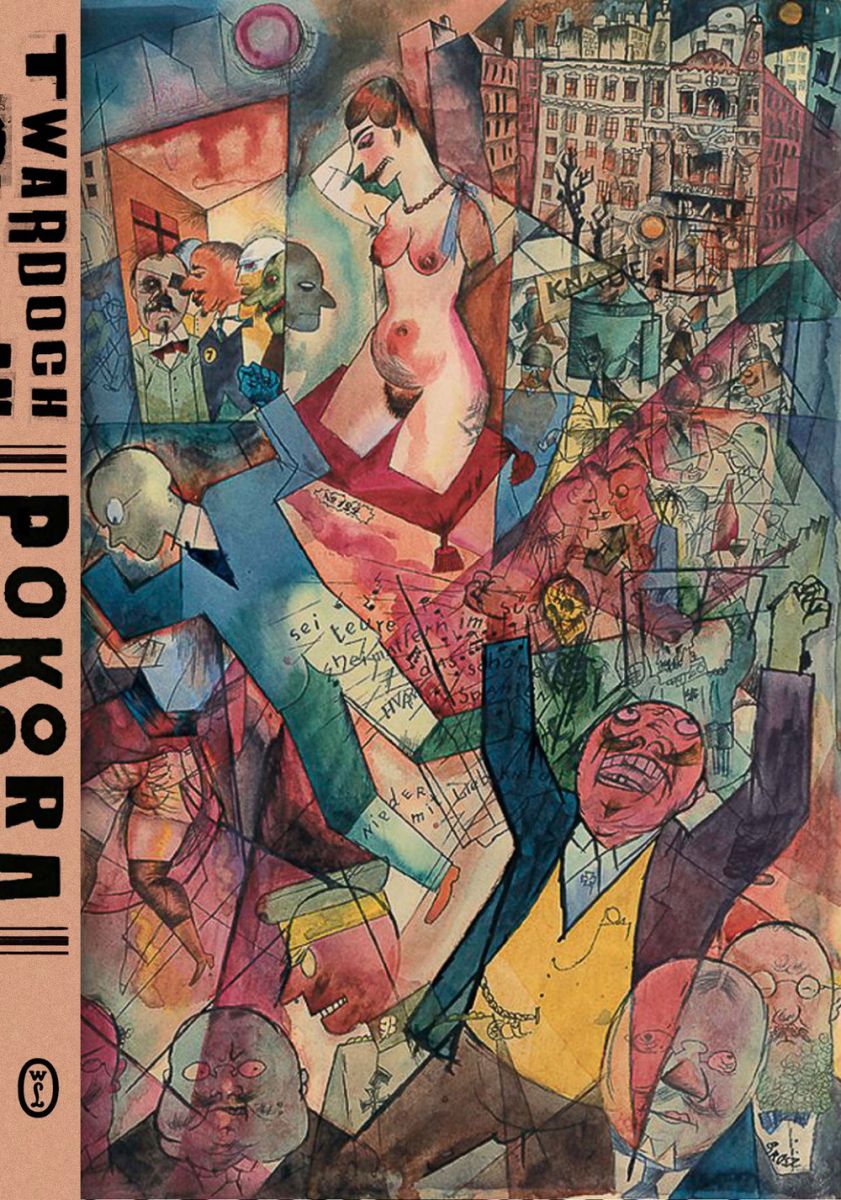

In Humbel, Twardoch takes up topics explored in his earlier works. We’ll find here issues of Silesian identity tangled up in conflicts between Poles and Germans; fratricidal struggles, from which no winners emerge; the sufferings of individuals caught up in the turbulent maelstroms of history; male desires; and finally, the figure of the femme fatale. The author impresses with his sensitivity to detail and psychological insights, but above all with his rare ability to sustain a narrative and intrigue. Thus, readers aren’t given an elegant yarn spun around the decoration of the era or a moralising treatise on the subject of the fluid identity of Alois Pokora, who is wounded in the French trenches of the First World War, but a full-blooded novel with a generous helping of 20th-century history of Silesia peopled by well-drawn protagonists.

Humbel may call to mind to an extent Pierre Lemaitre’s Prix Goncourt-winning novel The Great Swindle, although with regard to its universal – literally parabolic – dimension it’s closer to another work set during the First World War: Erich Maria Remarque’s classic novel All Quiet on the Western Front. As with Remarque, history touches everybody here, even if they gamely try to give it the slip.

Krzysztof Cieślik

Translated by David French

Learn more about other New Books from Poland

***

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”