Popiełuszko’s death suffered at the hands of Communist Security Service remains a mystery to this day

For the clerics, not only the raw living conditions, but also the intense system of punishments, were extremely oppressive. One also should consider the poor nutrition. Three meals a day, small portions, and a repetitive menu. If a meat dish ever appeared on the table it was sausages, and with premeditation, it would be served on Fridays when the clerics would be abstaining from meat products. It was known that they would not eat and they were punished for it. Popiełuszko once had to endure a thirty kilometre march. And when the soldiers were late returning from exercises, the food was standing cold on the table and that’s how they would have to eat it. All of this had a negative effect on the health of the divinity graduates.

Likewise, there was hard labour, often beyond their strength. For example, the clerics were assigned to construction work. One of them remembers, ‘We were extremely tired, could not sleep at night because tanks were on the move and the mosquitoes were biting. On the second day this was repeated. The tanks were on the move, followed by ammunition trucks. Then came the pontoon squad from Żagan, our old friends, with whom we built several bridges.’ Another time they were assigned to work in the fields. ‘Work on a 700 hectare farm, work with no end. Wheat and wheat. Day and night. Work with sacks and with straw. Very tiring…’

At the same time, medical care in the army left much to be desired. There was a doctor’s office, but in theory only. It was hard to say if one could get professional medical treatment there. Past friends of Fr. Popiełuszko remember to this day how every divinity graduate who fell ill and went to see the local doctor, received the same one pill, labelled ‘for sore throat’. It did not matter what the complaint was.

‘Soon we stopped going to see the doctor,’ remembers Fr. Wasiński.

It may be that this situation was caused by instructions issued by Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski, which demanded the greatest suspicion when dealing with the clerics and recommended that ‘attention be paid to frequent cases of simulated illness by divinity graduates, especially in the early phase of their service time. Each case of a divinity graduate soldier being sent before a medical committee should be preceded by an alert to the deputy political unit commander, who then is obliged to personally inform the head of the proper medical committee about the fact that the illness in question may be simulated.’

As time went on, the need for medical attention definitely grew, especially in the winter when the officers would not permit the clerics to put on warm clothing and these young men started to catch influenza en masse. Fr. Dusza remembers how on November 1, 1966 there was a sudden onset of harsh winter during which frost nipped fiercely at their faces. Meanwhile, the divinity graduates were not allowed to wear even a neck scarf.

‘The soldier is not a Christmas tree!’ the officers told us.

And at the same time they showed their extreme cynicism.

Fr. Jerzy was also among the sick. His friends noticed that his body was getting weaker. Popiełuszko had asthma, which started to show itself especially when he had to wear a gas mask, as then he would start to choke. He had no strength to run in the snow, and such orders were given to torment him further. ‘The more sweat during exercises, the less blood spilled later in battle,’ said the officers in justification.

Fr. Dusza confirms that Popiełuszko’s state of health was gradually getting worse. This did not halt further repressions. Sometime later, after an extended time spent standing for an hour in the freezing cold (during the so-called ‘toughening up sessions’ in the morning) he went to the doctor with a fever. But no treatment was given.

Excerpt translated by Peter Obst

Popiełuszko’s death suffered at the hands of Communist Security Service remains a mystery to this day

Translation rights: Znak Publishers, bolinska@znak.com.pl

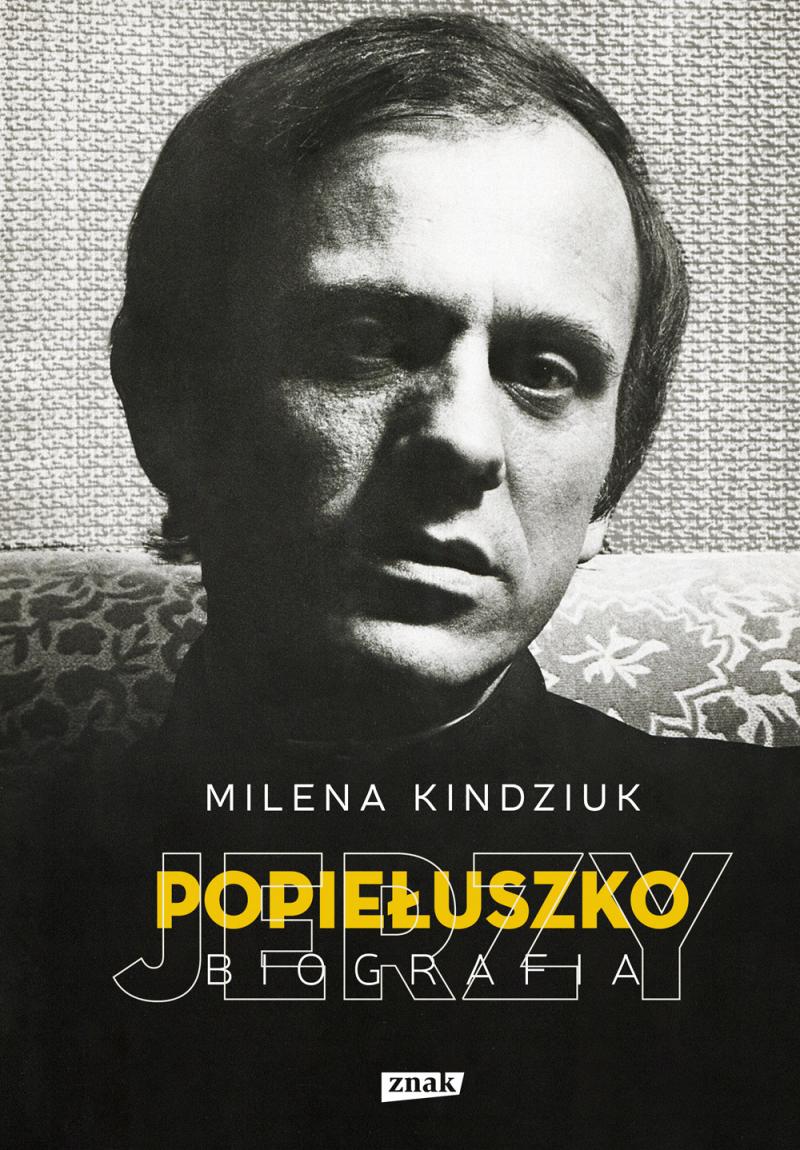

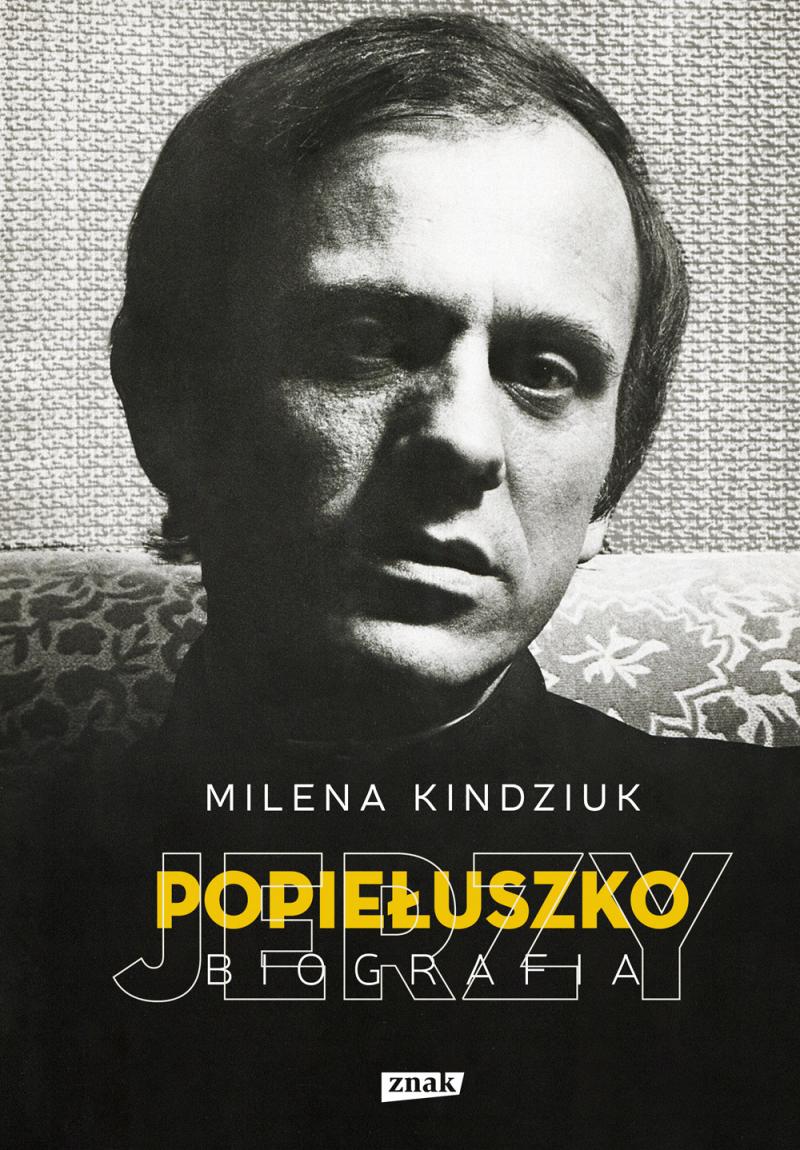

This biography of Fr. Jerzy Popiełuszko – beatified on June 6, 2010 by the Roman Catholic Church – is a comprehensive story of his life and activities. The composition of the book is defined by a chronology of events: from childhood in a peasant family in Podlasie, through seminary studies and pastoral work in Warsaw, to a martyr’s death suffered at the hands of Communist Security Service officers and the events leading to his beatification process. Rich photographic material and a section consisting of letters and documents form a valuable complement to the whole.

The subject of this biography still arouses great interest in Poland and the world for several reasons, which are discussed in the book in an interesting manner. Above all, his death remains a mystery to this day – for it is not known who ordered his political murder. Fr. Jerzy Popiełuszko is also an intriguing witness to faith – an ardent, self-sacrificing and caring priest, very much loved by those around him, who maintained a serenity of spirit despite harassment by the political police and the constant threat of death. His writings, interesting as a testimony of the times, have universal dimensions – reflections on the fate of man, his freedom and its endangerment. Finally, Jerzy Popiełuszko’s activities are a fascinating example of heroic resistance, as they were devoid of any prospects for success against a repressive state.

Milena Kindziuk’s book also gives an insight into the life of Poles under Communist rule. One example is her portrayal of the Podlasie village, where the protagonist of the story grew up and the special military unit for seminarians in which he first experienced persecution. The heritage of the family home – reconstructed through the author’s interviews with parents and relatives of Jerzy Popiełuszko – provides the reader with an important context that helps in understanding his choices and decisions.

The main part of the biography concerns Fr. Popieluszko’s pastoral work combined with his civil and patriotic involvement during the years when the Solidarity social movement took root in Poland. So it is also a story about the historical nuances of the Solidarity movement and the lives of the people who made it happen.

Tomasz Garbol, translated by Peter Obst

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”