More than a catalogue and more than a biography or an academic study – much as Szukalski was more than an artist

In April and May of 1916, and again in May, 1917, the Art Institute of Chicago held two solo exhibitions of the work of Stanisław Szukalski. The first exhibit was devoted to his best drawings and sculptures, while the second featured drawings and graphic art. At both openings the artist displayed his penchant for outlandish behaviour. At the first, he publicly destroyed the awards he had been given, claiming that the jurors were not qualified to evaluate his work. A year later, protesting an attempt to censor A Man and His Brother, a drawing with an anti-British slant, Szukalski tore his works from the wall and ripped them to pieces, after which he proceeded to destroy the furniture in the museum lobby, declaring ‘either all of my drawings will be displayed, or none of them.’

Szukalski’s shocking behaviour at his two Art Institute exhibitions, and in particular, his spite for the academic principles of this hallowed, yet conservative municipal cultural institution, won him a certain popularity among young artists, indirectly paving the way for the emergence of new concepts in American art. Realizing his popularity was on the rise, Stanisław Szukalski began attaching great importance to his physical appearance and his gait. He was taller than average (174 cm), with a large head crowning a short neck, and a face with symmetrical feminine features, framed by long, gently wavy hair; he wore corduroy pants with a leather belt five or six inches wide, and carried a heavy stick in his right hand. He walked with a jaunty step, swiftly and decisively, taking long strides (his childhood memories include strolls with his father, who forced him to keep pace with the adults).

Stanisław Szukalski’s implacable, even hostile response to his critics, as well as his reluctance to sell his works (he dreamed of donating them all to the reborn Polish nation), meant that he tended to be short of money for food, and often went hungry. Unexpectedly, on 31 May 1922, without having announced the fact to many of his acquaintances, he wed Helen Louise Walker, an amateur painter, the daughter of Samuel L. Walker, a wealthy and respected Chicago physician. Although his father-in-law was thought to be a millionaire, Szukalski took no money from him. Yet, on his first wedding anniversary, the local Covici-McGee publishers released a luxury-bound album entitled The Work of Szukalski in a limited run of one thousand copies. The book contained colour and black-and-white reproductions of the artist’s sculptures and drawings, photographed by himself, as well as an autobiographical note and his own brief commentaries on his works, which took the form of peculiar parables and aphorisms. The Chicago Literary Times ran an ad for the volume, calling it ‘the most beautiful and remarkable book ever published in the United States.’

Excerpt from the introduction by Lechosław Lameński, translated by Soren Gauger

More than a catalogue and more than a biography or an academic study – much as Szukalski was more than an artist

Translation rights: Fundacja Evviva L’Arte, fundacja@evvivalarte.org

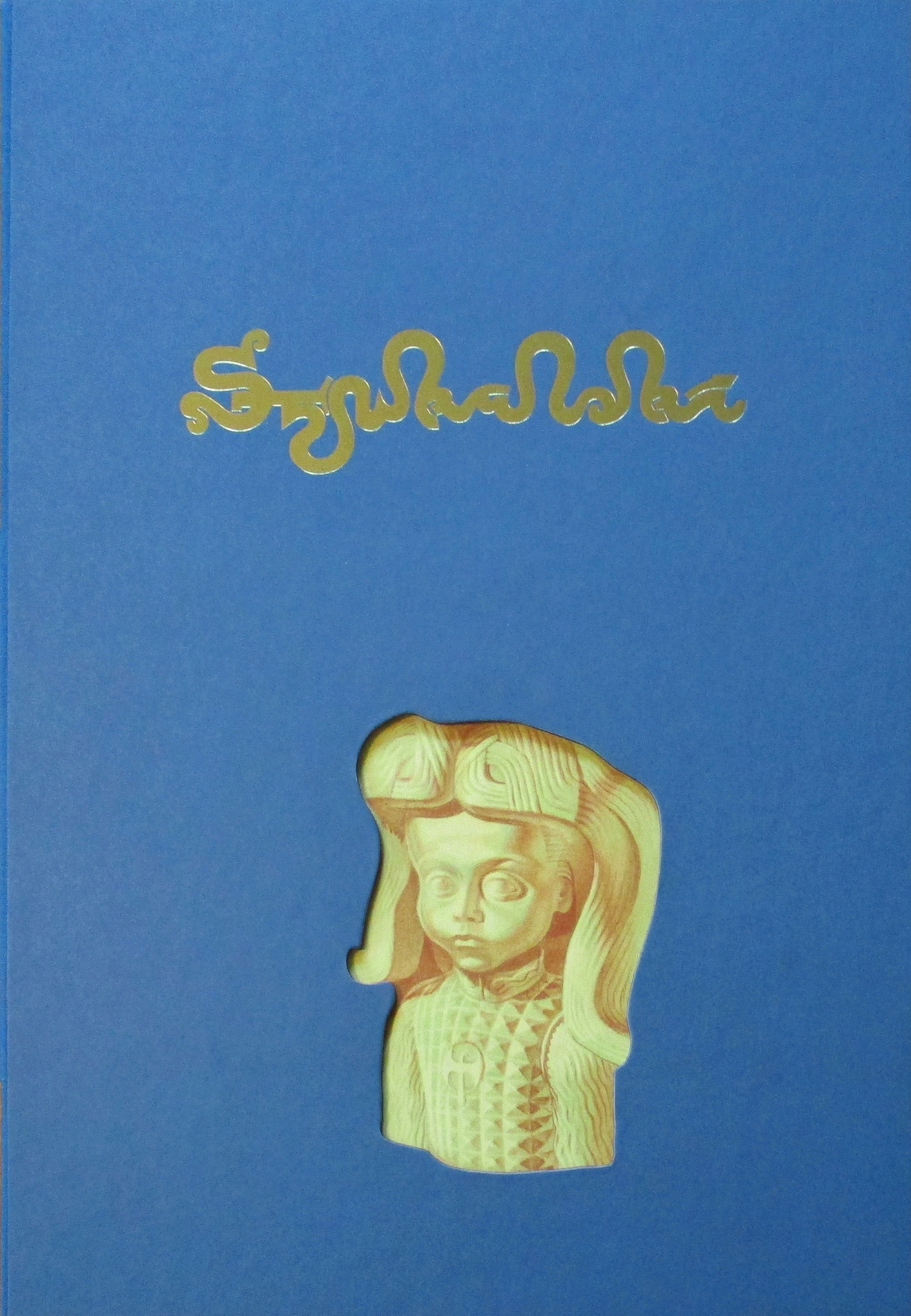

The Evviva L’arte foundation album devoted to Szukalski is an art project unto itself. The work and life of Stanisław Szukalski is on display in this unusual catalogue of his work, shown through a series of documentary photographs framed with text. The central figure of this publication is an artist who remains underappreciated in the official canons of art history – overlooked by those who create the permanent collections of museums – but who is increasingly present in pop culture. The boisterous life of ‘Stach from the Warta [River]’, as he preferred to be called, more resembles an adventure film than the biography of a real person. A young genius whose talent was discovered very early on, Szukalski was forever at odds with both critics and the arts community at large, often misguided in his choices and political affinities, but always capable of gathering a group of fanatical devotees around him. He was the creator of a complex mythology centred on Poland, a remarkable iconography, a new history and even experimental linguistics. A sculptor and designer of monuments, most of whose works were destroyed (or never realised); an inhabitant of Krakow, Paris, and Los Angeles, warmly remembered by Leonardo DiCaprio (who knew him as a child, through his father), Szukalski indeed seems a character plucked from a novel. The authors of this publication have not, however, succumbed to the temptation to fictionalise or mythologise. This reliable biography, interesting in itself, is accompanied by a methodologically astute description of his work and its reception, while the author of the afterword attempts to answer a still- pertinent question: ‘Why do we need Szukalski?’ There are also some brilliant photographs of works both extant and vanished: designs, drawings, and pictures, all laid out splendidly. All this makes the volume much more than a catalogue, more than a finely published coffee-table book, and more than a biography or an academic study – much as Stanisław Szukalski was more than an artist.

Hanna Wróblewska, translated by soren Gauger

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”