A saint who walked in sandals and slept under the same roof as villains, drunks and whores

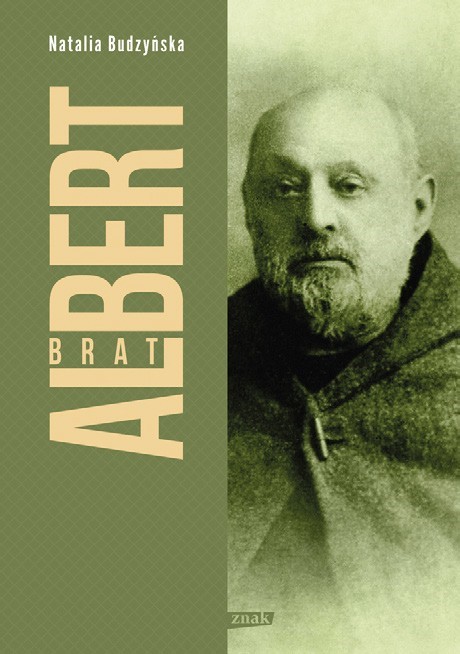

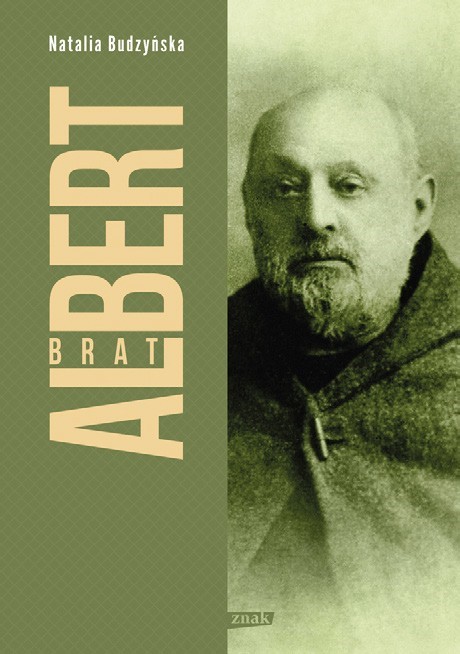

To me, these images in no way suited the Brother Albert whom I began to know. After all, he was never, even for a moment, an old softie. The love with which he surrounded the poor and all those around him was manly and radical, demanding and forgiving. Or, put simply, fatherly. That’s why I love the photograph showing him holding a cigarette. In it he seems accessible, real, genuine. Looking at it, I can feel the sun’s warmth, smell the grass and the cigarette smoke. I hear a babbling brook and feel myself shooing away flies. I imagine that if I touch his habit, I will feel its roughness. I could sit on a bench by the wooden wall and simply have a chat with him. I wonder if this is the photograph where he was caught off guard by the photographer of General Zamojski’s wife. Most proba- bly aware of Brother Albert’s aversion to cameras, she tricked him into having it taken. Knowing that he was coming to visit her, she instructed her photographer to stand in a specific spot and to take his photograph without asking, out of the blue. This ruse did not amuse Brother Albert, in fact he was angry with her. But maybe thanks to this cunning plan, we now have a Brother Albert that we can reach out to with our hand, approachable and human. So much so, that, at any moment now, I feel he will lower his head, look sideways, tap the ash from his cigarette, turn around and simply walk off, out of the frame.

(…) He loved his tramps and paupers. He was able to find a common language with them. He didn’t condemn them. He didn’t moralise. He didn’t evangelise. He was able to speak with them, share a joke, offer them vodka and a cigarette. In each of them he saw a human being and sought to find their virtues, whilst describing faults with humour. He didn’t take himself too seriously. As observed by Countess Tarnowska: “It is hard to believe that this highly cultured person, living day and night in the most appalling physical and intellectual conditions, in indescribable poverty, in surroundings so unlike those to which he was ac- customed as a gentleman and an artist, could retain in similar company his colourful and rather amusing manner of speaking on any subject, including his own problems, in such a way that often when in his presence, one would laugh heartily upon hearing about the adventures and opinions of his nocturnal guests, or his own efforts and even his disappointments, whether this be during a request for donations, or among honorationes of various standing”. Celina Bzowska also noted: “Brother Albert’s face radiated with amusement when he told his stories. He became energised, illustrating everything with his tone of voice and movements. He relished the abilities and qualities of his charges”.

Some people were unable to stomach these accounts. Such a reduction to the level of the lowest of the low did not suit them. They said that Brother Albert sheltered drunks at night and cared for thieves. When local councillors insisted on a response to these char- ges, Brother Albert replied that, yes, he will continue to open his gates to alcoholics knocking in the middle of the night and, no, he will not pretend to be a poli- ceman, and therefore had no intention of informing on thieves. They then asked him directly whether he would accept a murderer who had just attacked somebody. He replied that, yes, of course he would, adding that at least the murderer wouldn’t hurt anybody while in his care. He reiterated that mercy is more important than rules and regulations.

Excerpt translated by Daniel Wiśniewski

A saint who walked in sandals and slept under the same roof as villains, drunks and whores

Translation rights: Znak Publishers, bolinska@znak.com.pl

The lives of an eccentric and a saint have much in common. If you represented each one as a line on a graph, they would both would eventually fall away from the well-trodden path that the fate of most people follows (school, first love, studies, work, marriage, children). Whereas the first starts to go around in blind circles, like the trace of meticulously joined-up handwriting, the second ascends, following an upward spiral, to heights that are difficult to comprehend.

The first half of Adam Chmielowski’s life was typical for a Polish artist in the 19th century: the son of a good noble family, unfazed by working in the administrative apparatus of one of the foreign powers occupying Poland, eventually rebelling and becoming an idealistic student during the Spring of Nations. As a combatant in one of the tragically doomed uprisings against Russia, he was seriously injured and underwent an amputation without anaesthesia (his screams from an isolated forest hut were muffled by heavy snow fall).

Thanks to bribes and the help of influential relatives, he escaped from under the noses of the Russian authorities to become a student in Munich and Paris. It was an extravagant time of art models, wine, and top hats, mixed in with a hint of boredom. Then, following a Russian amnesty, he returned to Poland.

Suddenly, in 1880, the pen skids off the horizontal line and traces towards the heights. As a bearded monk, he walks in sandals, sleeps under the same roof as bandits, drunks, and whores. Philanthropists who, up until then, had given their charity wrapped in violet scented handkerchiefs (or, in the belief it was more hygienic, threw coins onto the pavement), could not understand him. We also do not completely understand how Adam Chmielowski could have become Brother Albert. This book attempts to provide, at least in some small way, an explanation.

Wojciech Stanisławski, translated by Daniel Wiśniewski

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”