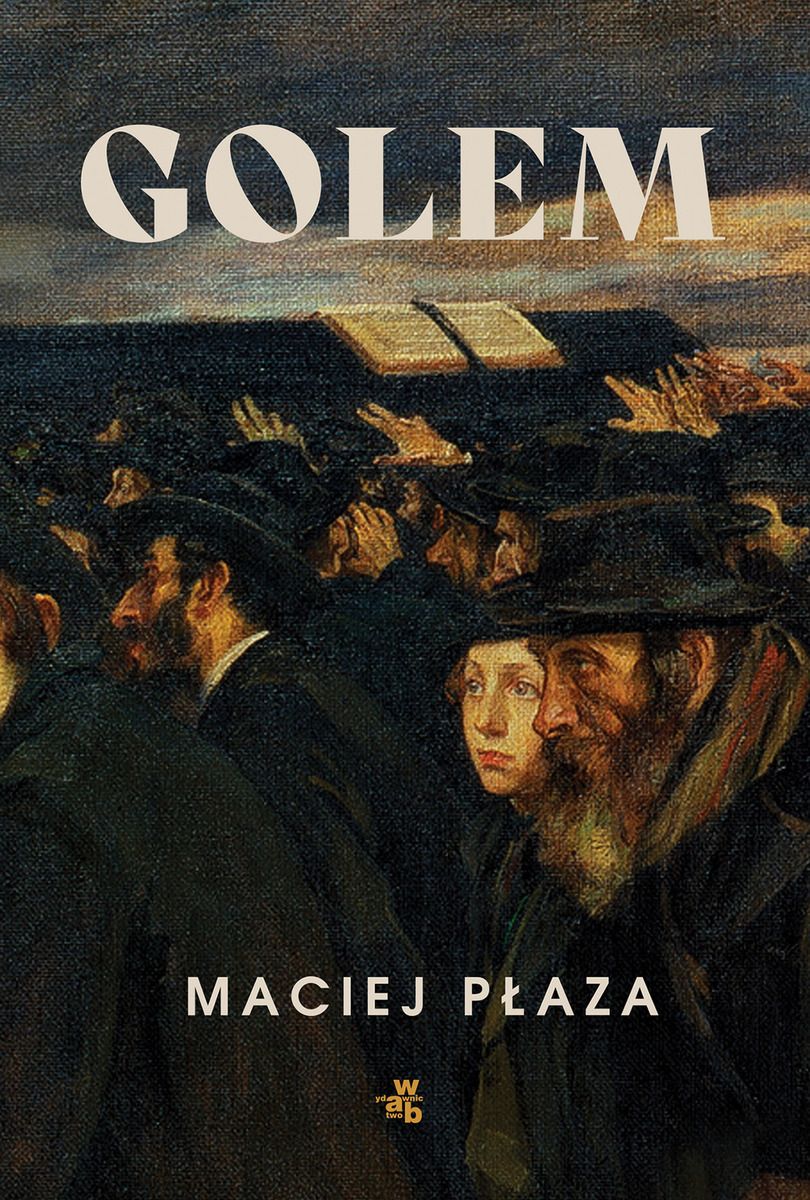

A story rooted in cabbalistic tales and sacred scriptures that belong to the Judaic canon

The people watched him trailing along the empty streets, a thin, pale hulk in large boots, as if they’d been pulled off someone bigger, though it wouldn’t be easy to find a person that size anywhere else but a circus wagon, in a coat soiled with the mud of roads unknown. He dragged his left leg over the stones and carried a sack on his back, with one hand tucked behind its drawstring. He walked with a limp, but without hesitation – not once did he turn his head to see if he was going the right way, but evidently knew where he was heading, though instead of walking straight to the specific spot he calmly wandered. He passed the Orthodox church, crossed the main market square, and on reaching the small marketplace he halted outside the synagogue that stood there, outside the qahal house, and then beneath the shamash’s cottage, as if he were the ragamuffin from the old joke, who when asked if he knows any important local person boasts that he knows the shamash, and the shamash knows the whole town. He turned a circle and finally came to a stop by the pump, where it was even more plain to see what a wreck he was. To drink the water, he didn’t lean forwards or squat like a normal person, but suspended his entire body above the pump, stooped, embraced it stiffly and pressed his large, muddy frame against it. He lapped the water from the palm of his hand, though as some had noticed, first he washed it and moved his lips for a while, perhaps muttering a prayer.

The people stared at him from behind their windows and fences. The talk was of why he’d come and who on earth he was. Probably not an itinerant beggar – he didn’t have the air of a beggar, and it didn’t look as if he were accustomed to asking for anything. Maybe a jobless ne’er-do-well? No, not that either, because his face, though coarse and sallow, was youthfully innocent; in any case, he hadn’t walked across the town like a vagrant, he hadn’t peeped about curiously to see who had what in their chamber or farmyard, or on their shop sign – he hadn’t look around at all. Nor was he a deserter, because he wasn’t trying to hide, he didn’t fear the eyes of agents or the tongues of informers. And definitely not a goy, because he was dressed the Jewish way, and even though he had no sidelocks and his beard was short, he had kugel written on his face. Perhaps he had come to see the tzaddik, bringing a note pleading for a prayer to the Almighty to restore someone’s health, but who would have set out on such a journey overnight? (…) His body was crooked, his skin was the colour of old canvas, just like his sack, his brow was lined with pain, his eyes clouded with lack of sleep and hunger. Across his cheek ran a scar, perhaps a birthmark, perhaps the trace of stitches sewn by the unskilled hand of a barber who’d spurred himself on with a glass of spirit alcohol. He whom God marks out He does not bless, said Reb Arje Szub, but the saintly tzaddik waved a hand to silence him. Reb, asked Reb Jakow Ber – who was adept at reading his gestures and carrying out the orders they concealed, with many years of training, handing the saintly man his pipe, cane, glass, book, pen, prayer book, tefillin and tallit, and commanding quiet before prayers; Arje only led the singing, as the chief cantor and master of the Hassidic nigunim – Reb, repeated Reb Jakow, who is this fellow, do you know him? For a time the saintly man said nothing, then he nodded inquiringly in the stranger’s direction. Where do you come from? asked Jakow. Are you a Hassid? Are you on your way to your tzaddik? Where is he from, where does he live? In Międzybóż, Czarnobyl, Stepań or Ołyka? At these questions the stranger merely goggled; it was plain to see that he couldn’t hear a thing. One of the Hassidim clapped without warning by his ear, but the lad didn’t even shudder. Suddenly from somewhere far away, possibly from the pastures by the river, came the fierce barking of a dog. The boy tilted his head and listened intently. He’s faking, snapped Jakow, but once again the tzaddik ordered silence. The stranger was mumbling something. His lips were almost motionless, and yet he was muttering indistinctly, and after listening for a while the Hassidim caught some familiar words: Wretched am I and dying of the shivers, I have endured Thy wrath, I am falling, Thy fires have run through me, Thy terrors have broken me.

Excerpts translated by Antonia Llyod-Jones

A story rooted in cabbalistic tales and sacred scriptures that belong to the Judaic canon

Translation rights: Foksal, krystyna.kolakowska@gwfoksal.pl

Maciej Płaza’s novel must be the product of a fascination with a world that no longer exists. It’s about a small, closed society of Hassidic Jews, typical of the cultural landscape of Poland in the past, especially the small towns situated within its south-eastern borderlands. In one of these places, early in autumn 1911, a strange man appears, a repulsive-looking vagrant. He’d have been chased away at once, if not for the intervention of the local

tzaddik, who recognises the stranger as a holy man, perhaps an envoy of God Himself. So the tzaddik names the stranger Rafael and lets him stay at his manor; the man forms numerous relationships with the residents of the shtetl and becomes familiar with the local conflicts – the ongoing quarrels and those that have occurred in the past. This gives the novel’s readers the opportunity to learn about the culture and mores of the Hassidim – they’re presented with a sea of knowledge about Hassidic religious practices, established rituals, unusual imperatives and prohibitions. What makes Płaza’s story exceptional is that it is rooted in cabbalistic tales and sacred scriptures that belong to the Judaic canon. For Płaza is most strongly drawn to themes concerning Jewish mysticism, which he endeavours to reinterpret in his own way. In the world of the novel this interest is explored through a debate on the possibility of the Messiah appearing on Earth. There are those who maintain that Rafael is the Messiah. Whereas the eponymous Golem, moulded from clay in the shape of a man, appears towards the end of the story and is also an attempt at reinterpreting this highly familiar figure from Jewish legends. When the Hassidim in the town where Rafael suddenly appears are threatened by a pogrom, the tzaddik and his assistants mould and animate the Golem, who routs the people taking part in the newly launched pogrom. Equilibrium is restored, and not without the involvement of Rafael himself.

Dariusz Nowacki

Translated by Antonia Llyod-Jones

Selected samples

She climbed her first peaks in a headscarf at a time when women in the mountains were treated by climbers as an additional backpack. It was with her that female alpinism began! She gained recognition in a spectacular way. The path was considered a crossing for madmen. Especially since the tragic accident in 1929, preserved … Continue reading “Halina”

First, Marysia, a student of an exclusive private school in Warsaw’s Mokotów district, dies under the wheels of a train. Her teacher, Elżbieta, tries to find out what really happened. She starts a private investigation only soon to perish herself. But her body disappears, and the only people who have seen anything are Gniewomir, a … Continue reading “Wound”

A young girl, Regina Wieczorek, was found dead on the beach. She was nineteen years old and had no enemies. Fortunately, the culprit was quickly found. At least, that’s what the militia think. Meanwhile, one day in November, Jan Kowalski appears at the police station. He claims to have killed not only Regina but also … Continue reading “Penance”

The year is 1922. A dangerous time of breakthrough. In the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic of Poland, Bolshevik gangs sow terror, leaving behind the corpses of men and disgraced women. A ruthless secret intelligence race takes place between the Lviv-Warsaw-Free City of Gdańsk line. Lviv investigator Edward Popielski, called Łysy (“Hairless”), receives an offer … Continue reading “A Girl with Four Fingers”

This question is closely related to the next one, namely: if any goal exists, does life lead us to that goal in an orderly manner? In other words, is everything that happens to us just a set of chaotic events that, combined together, do not form a whole? To understand how the concept of providence … Continue reading “Order and Love”

The work of Józef Łobodowski (1909-1988) – a remarkable poet, prose writer, and translator, who spent most of his life in exile – is slowly being revived in Poland. Łobodowski’s brilliant three- volume novel, composed on an epic scale, concerns the fate of families and orphans unmoored by the Bolshevik Revolution and civil war and … Continue reading “Ukrainian Trilogy: Thickets, The Settlement, The Way Back”