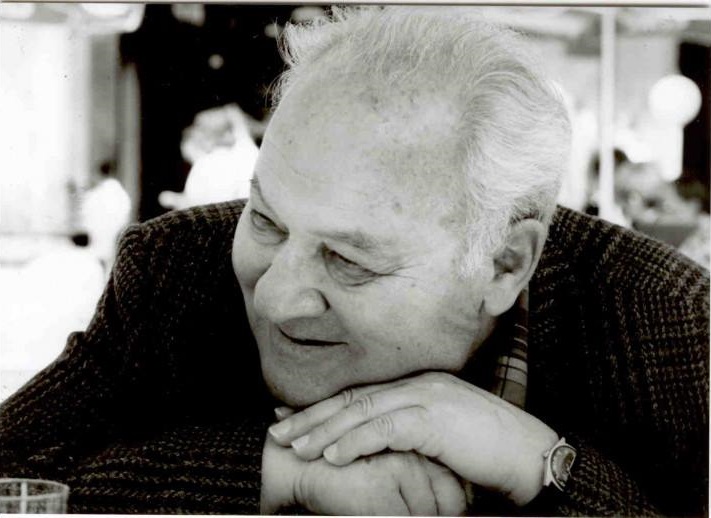

Gustaw Herling-Grudziński was one of the most popular Polish writers and journalists, author of memoirs (A World Apart), diaries (Journal Written at Night), journalistic texts (including Upiory rewolucji [Specters of Revolution]), essays (Six Medallions and Silver Casket), and novels (The Invincible Prince).

He was born on May 20, 1919, most probably in Kielce (in his publications he stated that it was Kielce, while his birth certificate shows the village of Skrzelczyce as his birthplace), a son of the owner of a small demesne near Busk.

Two years later, his father sold the demesne and bought a mill in Suchedniów, where Gustaw lived together with his mother and siblings. He studied at the Mikołaj Rej Gymnasium in Kielce, where he edited the school newspaper “Młodzi idą” (“The Young Are Coming”). In 1935, he made his debut in the magazine “Kuźnia młodych” with a reportage titled Świętokrzyszczyzna [“The Świętokrzyski Region”].

“Pictures and landscapes from my childhood keep coming back to me, and if they do – it means that they are stuck somewhere very deep inside me. That is why I insist on the idea of “small homelands”. I do not think then about Poland, which as a country is too “wide” to be covered by such feelings, but about a specific region of my youth. I have never been able to describe it the way I would like to.”

(Najkrótszy przewodnik po sobie samym [“The Shortest Guide to Myself”])

After graduating from school (1937), he was accepted into Polish philology studies at the University of Warsaw, where he studied until 1939. He contributed then for the magazines “Ateneum”, “Pion”, and “Pióro”; he was also the editor of literary sections in the magazines of the Polish Democratic Youth: “Przemiany” and “Orka na Ugorze”. He also participated in meetings of young literary critics gathered around Ludwik Fryde. He published (in “Pion” and “Ateneum”) critical literary studies on, inter alia, Maria Dąbrowska and Czesław Miłosz.

After the beginning of the war, together with his friends, he founded the Warsaw underground group PLAN (Polska Ludowa Akcja Niepodległościowa – Polish People’s Independence Operation). He also co-edited the first issues of the underground magazine “Biuletyn Polski”. In December 1939, he crossed the demarcation line and reached Lviv, where, thanks to the patronage of Maria Dabrowska and Juliusz Kleiner, he was accepted into the Writers’ Union. Thanks to this, Herling-Grudziński gained a safe conduct pass that made his life easier until the Soviet authorities discovered that the Writers’ Union was not the same as the Soviet Writers’ Union. Then, the writer left for Grodno (where he worked in a puppet theatre), and in March 1940, he tried to get to Lithuania; however, the people who were supposed to help him turned out to be NKVD agents. Gustaw Herling-Grudziński was arrested and sentenced to five years in the labour camps. Placed successively in prisons in Grodno, Vitebsk, Leningrad, and Volograd, he was finally sent to a camp in Yertsevo, near Arkhangelsk. He worked as a porter at unloading wagons, often for almost thirty hours without a break. Six months after the conclusion of the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement, in January 1942, he left the camp after his hunger strike – he described his experiences from that time in his most famous book, A World Apart: A Memoir of the Gulag. Less than two months later, in Kazakhstan, he was conscripted into the Polish Army being formed in the USSR under the command of General Anders, with whom he reached Italy through the Persian Empire, Iraq (he published there in the magazine “Kurier Polski w Bagdadzie”), Palestine, and Egypt. After the Battle of Monte Cassino (for which he was awarded the War Order of Virtuti Militari), he moved with his corps to Rome. He was seconded to the editorial office of the “Orzeł Biały” weekly, where he was the head of the literary department. He also published in the magazines “Irydion” and “Kosmopolita”, as well as in the Italian magazine “Arteusa”. At that time, he married a painter, Krystyna Domańska, with whom he had a daughter, Marta.

In 1943, he met Józef Czapski and Jerzy Giedroyc. They were closely connected by friendship, a part of which was later cooperation. When the first issue of “Kultura” was created in 1947, Herling-Grudziński was its co-editor.

His book debut came at that time: in 1945, a collection of sketches by Herling-Grudziński Żywi i umarli (“The Living and the Dead”) was published. In his foreword to the volume, Józef Czapski wrote:

“Grudziński wants faith and hates eclecticism. Any choice, even if wrong, is better for him than no choice, he knows […] that everything that exists for man exists as a certain positive or negative value, that there are no morally neutral things.”

In 1946, he joined the Polish Socialist Party (from which he left in 1960, after removing his friend Adam Ciołkosz from the party). He published in the party magazines “Robotnik Polski” and Światło”. When in 1947, Jerzy Giedroyć decided to move the Institute of Literature to Paris, Herling- Grudziński left Rome and went with his wife to London. He made contact with the editor of “Wiadomości”, Mieczysław Grydzewski. On the pages of this magazine were published his Dziennik podróży do Burmy (“A Journey to Burma: Journal”) and excerpts of memoirs from his stay in the Soviet Gulag, collected and published under the title Inny świat. Zapiski sowieckie in 1951 in English (the English title read A World Apart: a Memoir of the Gulag, the foreword was written by Bertrand Russell, and the book was translated by Adam Ciołkosz’s son, Andrzej. The Polish edition was published two years later, also in London). The cooperation with “Wiadomości” lasted until 1953, when the Grudziński family moved to Munich. The writer headed the cultural department of Radio Free Europe there. In the same year, his wife committed suicide. Two years later, together with his second wife, Lidia Croce, he returned to Italy, settling in Naples, where their son Benedetto was born. He then re-established cooperation with the Literary Institute and “Kultura” magazine. The Parisian Institute published further books by the writer: short stories Skrzydła ołtarza (“The Wings of the Altar”, 1960) and Drugie przyjście (“The Second Coming”, 1963), critical texts on Russian literature, Upiory rewolucji (“Specters of Revolution”, 1969). In 1971, Dziennik pisany nocą (“Journal Written at Night”) began to be published, and it was later continued (until the writer’s death) in the “Rzeczpospolita” daily, published by Giedroyc as a book in 1980 (the years 1973-1979) and 1984 (the years 1980-1983). From 1981, Herling-Grudziński also began to contribute to the Italian press, including “Tempo Presente” and “Corriere della Sera”. He died in Naples on the night of July 4-5, 2000.

The work of Gustaw Herling-Grudziński was banned from print in Poland until 1988 (his books were solely published in underground publishing houses); then, Wieża i inne opowiadania („The Tower and Other Short Stories”) was published in the first circulation. Although he spent most of his life abroad, he occupies one of the leading positions in Polish literature.

He was a writer of very broad horizons – he wrote essays, short stories, reportage, diaries, reviews, and critical literary texts. The variety of subjects he touched upon is astonishing, yet he always touches upon people to some extent, different dimensions of their lives: from suffering and moral decline in the Soviet camps, through aesthetic admiration for works of art, to reflection upon metaphysics.

“For Herling, work and life, art and the fate of the artist, thought and condition of the thinker are not two separate zones, each governed by its own rules, but one whole, one reality, which requires from the person who wants to come into contact with it, a personalised relation, which is characteristic of relations between persons.” [Prof. Paweł Rodak]

A World Apart published in 1951 (in English translation, the Polish edition was published in 1953 by Gryf publishing house in London, and then in 1988 by Czytelnik publishing house) was one of the first and best literary works on this subject. Written in a reportage style, the memories of a stay in a gulag are a moving document of life in a labour camp, and, at the same time, a reflection upon the limits of morality, the fall of human dignity, the strength of overcoming adversity, and an analysis of totalitarianism. A World Apart is a direct reference to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead. This is evidenced not only by the quotations and title taken from the Russian writer’s book, but also by the form, including the number of chapters and recurrent motifs.

“My A World Apart was created out of a need for truth. I wrote the truth because my fellow prisoners obliged me to do so. They said goodbye to me in words, “Write the truth about us.” [G.H-G, The Shortest Guide to Myself]

In his speech delivered in 2000, on the occasion of the awarding of the title of doctor honoris cause of the Jagiellonian University, Gustaw Herling-Grudziński mentioned that it is the duty of an artist to give testimony. This autobiographical tone can be found in almost all of the writer’s works. In his sketches, essays, and short stories (of which he wrote over fifty), he described exactly what he wanted to bequeath in human memory: literature and European art, but also political issues and stories exploring existential issues. Nor did he run away from the motifs of transcendence.

“[…] I guess my most important choice was to become a writer. And regardless of my previous writing before the war, this decision was made after I left the labour camp. That’s why I say to myself that as a writer, I was born in the labour camp”. [G.H-G, The Shortest Guide to Myself]

The stories of Gustaw Herling-Grudziński can be described as journalistic or chronicler’s, often in a form reminiscent of sensational or criminal prose, although the events described by him should be accompanied by an atmosphere of uncanniness, resulting from the author’s fascination with whatever constitutes the immaterial side of humanity.

The writer constructed these stories on the basis of real or seemingly real events, most often set in a more or less distant past. This imbalance of realism, the impression as if the stories described had actually happened, is the result of a precise indication of their time and place, and the ease with which they can be associated with real situations and interests (art history, Mediterranean culture) from the writer’s life.

In the short story The Tower, the main character who is the narrator of the story goes on holiday to a house in Piedmont, where a deceased relative of his friend’s lived. The protagonist’s presence in this place becomes the starting point for two parallel stories – an unusual story about a resident of a nearby tower, who is suffering from leprosy, and a deceased teacher who had previously lived in this house. Both stories, as well as the character of the narrator, are connected by a choice of loneliness, a conscious isolation from the world and people. In a similarly sentimental atmosphere, other stories by Herling-Grudziński take place: Cmentarz południa (“The Noonday Cemetry”), Portret wenecki (“A Venetian Portrait”), and Pieta dell’Isola. Death is not the ultimate annihilation in them – those who have died are constantly reborn in the memories (and sometimes in dreams) of the living. They are represented by the narrator-protagonist himself, who explores the stories of the ruined house of two lovers, a portrait from Venice, hiding the tragic story of a mother and son, or a bricklayer who has lost his sight, hearing, and speech. In the short stories of Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, there are no explicit judgments or explanations. The metaphysical issues are barely outlined, left to the reader for their own consideration.

“Without much risk, one can probably say that […] metaphysical sensitivity is the key to this rich works. The whole vision of reality is metaphysical in Grudzński’s work. He humbly reflects on what is unnamed and escapes cognition. He is aware that human fate has its transcendent dimension, which people more and more often cannot recognise. [Zdzisław Kudelski, Studia o Herlingu-Grudzińskim (“Studies on Herling-Grudzński”)