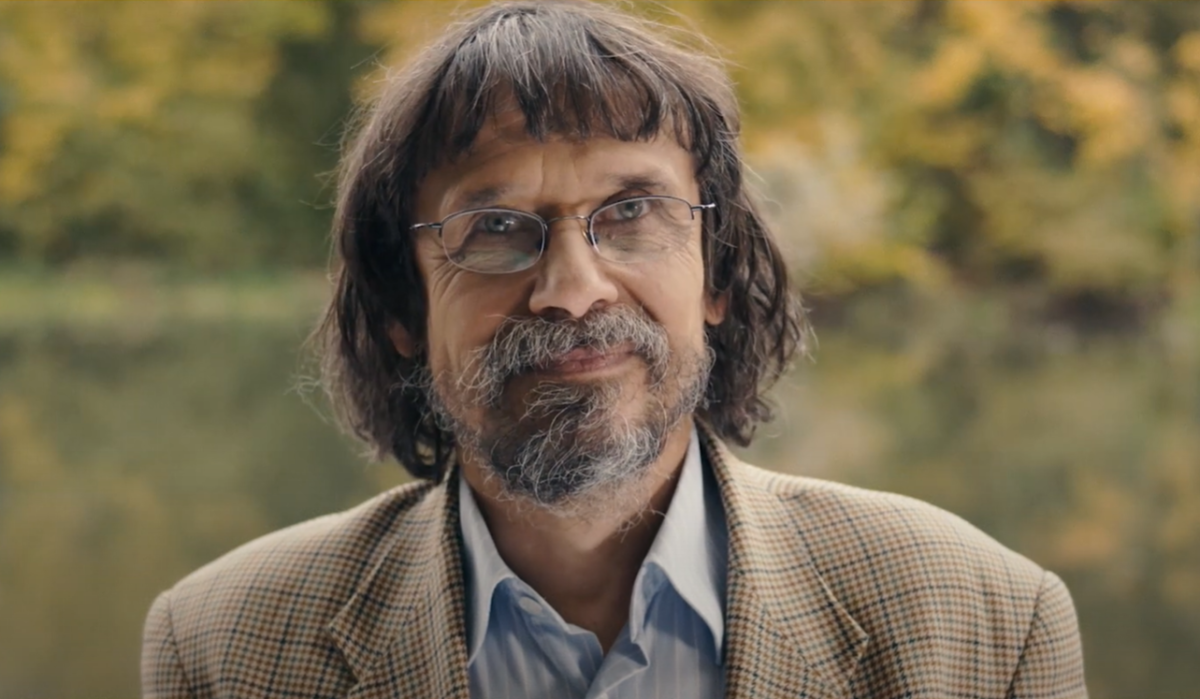

born in Warsaw in 1956, graduate of Law at the University of Warsaw, prose writer, playwright, literary critic, publisher, editor. From the 1970s to the 1980s, he was active in the anti-communist opposition.

From 1977, he was a collaborator of the Independent Publishing House, and from 1978 until the declaration of martial law, he managed the Independent Publishing Cooperative I. From March 1981, he was an employee of the National Coordination Committee of the Independent Students’ Union. From January to August 1982, he was interned. In December 1982, together with Jarosław Markiewicz, he founded “Przedświt”, one of the most important underground publishing houses of the 1980s. In May 1984, he was arrested; he was released by virtue of amnesty in August the same year. After 1989 (until 2001), he continued the activity of “Przedświt” publishing house. In 1995, in a gesture of protest, he resigned from work at the Warsaw prosecutor’s office.

He is a prose writer penetrating the ‘uncharted areas of Polish history’ (Marek Nowakowski). He published his first novel Lament nad Babilonem (Lament over Babylon) in 2003 and received a distinction award in the competition for the Józef Mackiewicz Literary Award. In this book, as one of the first authors in Polish literature, he portrays one of the Cursed Soldiers, breaking the stereotypes and clichés accumulated around this subject, referring, at the same time, to the model of realistic prose, successfully combining facts and even documents with fiction. Simultaneously, he renewed the convention of the biographical novel. In this novel, the plot is based on the fate of the main character, Tadeusz Danilewicz, but shown in a non-linear, snapshot, quasi-film way, creating a specific mosaic reflecting the drama of an individual in history, but also the opaque essence of history, especially of 20th century Poland.

History was the background of Holewinski’s subsequent novels and stories, in which, based on often fragmented accounts and documents, he reconstructed the dramatic fate of people rebelling against totalism, fighting for freedom, rebellious, uncomfortable, faithful to their values. At the same time, he asked questions about the importance of such values as honour, faith, Polishness, patriotism, courage, but also, for example, betrayal.

In the novel Opowiem ci o wolności (Let Me Tell You About Freedom), awarded with the Józef Mackiewicz Literary Award, he described the parallel biographies of two young Polish women, NSZ (National Armed Forces) soldiers, who fought in the Second World War against Germany, and were imprisoned after the war by the Secret Police. The protagonist of the novel Honor mi nie pozwala (Honour Does Not Allow Me) is Stanisław Ostwind-Zuzga: a Jew, legionnaire, policeman, soldier of the National Armed Forces and the National Military Union, one of the first victims of Secret Police. In the novel Szwy (Stiches) and short stories from the volume Nie tknął mnie nikt (No One Touched Me), modern Polish history and questions about the consequences of not having dealt with the reality of communism appeared.

The issues of the artist, art, and its relation to everyday life, as well as the vivid picture of the era, dominate the biographical novel Droga do Putte (Road to Putte) devoted to the Flemish painter Jordaens. On the other hand, in the psychological dramas from the volume Dyfuzja (Diffusion), the writer mainly analysed human attitudes towards evil.

Holewiński also engages in literary criticism. In the 1990s, he was a reviewer at ‘Gazeta Polska’, he also discussed the latest literature on Wnet Radio. From June to October 2016, together with Katarzyna Wójcik, he ran the literary program The Master and Catharina on Polish Radio Three. From October 2016, he has been the deputy head of the literary editorial office at Polish Radio Two. He also runs a reviewing column Mebluję głowę książkami (I Furnish My Head With Books) on the portal pisarze.pl. He is a member of the Polish Writers’ Association (he was the deputy head of the organisation in 2008-2011), the Polish Journalists’ Association, as well as the Free Speech Association.

Novels:

- Lament nad Babilonem, Warszawa: Prószyński i S-ka, 2003; 2nd edition in 2013.

- Za późno na modlitwę, Warszawa: Prószyński i S-ka, 2003.

- Przeżyłem wszystkich poetów, Warszawa: Prószyński i S-ka, 2004.

- Choćbym mówił językiem ludzi i aniołów, Warszawa: Prószyński i S-ka, 2005.

- Droga do Putte, Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, 2007.

- Opowiem ci o wolności, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka Wydawnictwo, 2012.

- Szwy, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka Wydawnictwo, 2013.

- Honor mi nie pozwala, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka, 2015.

- Pogrom 1905, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka, 2018.

- Pogrom 1906, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 2019

- Oraz wygnani zostali, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 2020

- Pogrom 1907, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 2020

Short stories:

- Nie tknął mnie nikt, Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza „Agawa”, 2008.

Drama:

- Dyfuzja i inne dramaty, Sulejówek: Agencja Dramatu i Teatru, 2006.

Film scripts:

- Historia Roja (co-author, film premiere March 2016, the author obtained the court order to remove his name from the film due to excessive changes in the script).

Other:

- Selection of Dzienniki of Krzysztof Mętrak, Warszawa: Iskry, 1997–1998.

Hungarian:

- A Puttéba vezető út: Jacob Jordaens festőművész életregénye [Droga do Putte], translated by Szenyán Erzsébet, Budapezst: Széphalom Könyvműhely, 2013

What are you currently reading?

In my rucksack, I have Josef Škvorecký’s All the Bright Young Men and Women translated by Andrzej Jagodziński. After that, I’ll go for Arystokrata ducha (Aristocrat of the Spirit) about Klemens Szeptycki. We all know about the two Szeptyckis, but there was a third one – Klemens, who was declared blessed. These are my two next books.

I’ve heard good reviews for Škvorecký. It’s about the film environment in the Czech Republic.

Yes, it’s film memories. I have read one third of the book and I can recommend it wholeheartedly. I have also just finished Łacińska wyspa. Antologia rumuńskiej literatury faktu (Latin Island. Anthology of Romanian Non-Fiction) translated by Bogumił Luft, also published by Karta publishing house. It’s a record of diaries and memoirs about recent Romanian history. Very interesting.

You read mainly Central-European literature, and it’s non-fiction.

It just happened, a coincidence. I receive tons of books because of my work on the radio. Yesterday, five of them came by mail. I also read a lot of prose. A day without reading a hundred pages is a day wasted.

Do you have to finish once you start?

For many years I did, not anymore. It happens often that after 60 pages, I put the book away, because I feel that it’s a waste of time. I have 10-12 thousand books at home, it is a horrific amount, and I already know that I won’t be able to read them all.

What helps you choose? Publisher’s reputation?

The author, and often the translator, is of primary importance. Because of my publishing activity, I know nearly everyone in the writing-translating environment. I know that if a translation is done by such translators as Andrzej Jagodziński or Michał Kłobukowski, I can assume they don’t waste their time on something bad.

I have recently read Zero K by Don DeLillo translated by Michał Kłobukowski. Superb reading, indeed.

There are translators who choose the books themselves and Michał Kłobukowski is one of them. And as for the writers, even the best names can be disappointing. There are authors whom I value and like, and yet I also put their books away after several dozen pages, because it turns out to be unreadable.

Recent delights?

I have fewer and fewer infatuations. When I was young, I would be delighted by many books, I absorbed them in the hundreds; meanwhile, today I am afraid of returning to them.

Who disappointed you after many years?

I’m afraid to pick up Dostoyevsky, whom I love. In the same way, I’m afraid of returning to Hesse, whom I adored when I was 19. His first book that I read and I value very highly to this day, Demian, I received it from my friend, a composer, Michał Lorenc. I am also afraid to pick up Bulgakov. And as for delights, the most pleasant surprises recently for me are Czech writers, whom I didn’t know before.

Fewer and fewer infatuations – is it a question of pickiness or is it more because there is fewer terra incognita on the map of literature for you?

Both. Today, I can judge quite quickly whether a book carries the values which can move me. And it is less and less often that I have the feeling that there is still something in literature that I haven’t seen yet.

Do you have any fascinations that did not survive the test of time?

If I were to read Steinbeck today, I’d probably be disappointed. A few years ago, I read his lesser known book, Travels with Charley. It was terrible, very bad. And I do remember that when I was young, The Grapes of Wrath made a huge impression on me.

Travels with Charley is a peculiar book. Reportage from a travel, during which Steinbeck allegedly struggled with an alcohol problem and he made up many things, just to write anything.

There is no need to publish everything, even if written by prominent writers. After many years, some things are published, and often their authors themselves did not want to publish them. This does deceased writers a great disservice.

And if something is truly valuable?

We should respect the writer’s will. And I know that now will appear the crowning argument about Max Brod, who, against Franz Kafka’s last will, did not burn his manuscripts. However, we all know how it works: a writer has their reputation and a famous name, so it guarantees sales, the family wants to take advantage, the publisher wants to take advantage and thus weird stuff is being printed. The flagship example is Marek Hłasko and his ‘discovered’ novels. This stuff is so bad…

Fully agreed. His youthful exercises cannot be read seriously.

I understand it might be important for academics, but showing it to a wide range of readers does not serve the writers well.

Any embarrassing books, which you read with flushed cheeks?

I was always very interested in history. I was born in 1956, so as a 10-year-old, I read a whole series of the so-called ‘books with tiger’ [Biblioteka Żółtego Tygrysa (Yellow Tiger Library), a historical series published by the Ministry of National Defence in the Polish People’s Republic from 1957 – ed.]. I didn’t realise then how much propaganda was in them. Of course, they also imparted some knowledge, but I can see today that it was supposed to shape young people ideologically.

What else did you read as a child?

Since my mum is a linguist, I had a weird inclination towards dictionaries.

Did you flick thorugh them?

No, I read them like novels. I was fascinated by language. Later, I read many dictionaries of writers, and this is how I shaped my literary taste. I saw in them titles and authors that I felt might be interesting for me.

Did someone at home suggest books for you?

No, not really. My older sister studied Polish Philology. One day, I took her reading list, and I guarantee you that Polish Philology in the 1970’s was different than it is now, and students had to read incomparably more. And it turned out that I had read roughly 80% of the books on this list, and I was still in high school. Then, at Law School, I had a friend with whom we raced at reading. We started attending Tomek Burek’s lectures in the Society of Scientific Courses, and later we even became friends. I had someone from whom I could learn.

Did your parents read?

Father was a technical scientist, he didn’t read fiction basically, whereas mum read an enormous amount. It is thanks to her that I had a chance to read books banned in Poland from an early age. As a 16-year-old, I read The Gulag Archipelago by Solzhenitsyn in its entirety. And very many Polish émigré writers.

The most important dissident writer?

Vladimir Bukovsky. I remember how shocking the impression his And the Wind Returns had on me. Perhaps it is a result of his outlook on life, and not just the literature. As far as Polish émigrés are concerned, Herling is the most significant writer to me. I truly regret never having met him. I began my adventure with his works with his books devoted to Soviet forced labour camps, about which I heard at home, since my grandfather experienced them as well. This is why they were almost private stories for me. But you asked me about recent delights, I have one thing.

I’m listening.

From six months ago. Józef Łobodowski’s Trilogy (a novel trilogy Komysze, W stanicy and Droga powrotna [Thicket, At Stanitsa, and Way Back] published by Test publishing house from Lublin in April 2018 – ed.). I was already acquainted with Łobodowski’s journalism, this trilogy, however, about Poles living in Russia from 1918, it was an extraordinary discovery for me.

Łobodowski during his lifetime was known more as a poet of two languages: Polish and Ukrainian.

He began with poetry and probably was the greatest eulogist of Ukrainian culture. His novels, though, are also absolutely unique. My second fascination is Nadberezyńcy (Berezina people) by Florian Czarnyszewicz, a novel, which, thanks to Professor Maciej Urbanowski, somehow returned to literary circulation. Interestingly, I read other books by Czarnyszewicz and they were weak, whereas Nadberezyńcy is a remarkable, great novel.

It happens sometimes that one masterpiece in life must be enough. Were we to look back at your youth, which authors were pivotal for you ?

I started picking up serious books very early. I was fourteen when I read Rabelais and Dostoyevsky. In 1982, it took me 8 days, it’s unbelievable, but it’s true, to read In Search of Lost Time by Proust (I had a lot of time then, I was in a hospital, where I had been taken from internment). But I still managed to be dazzled in later years. When I got to Rakowiecka prison in 1984 for my political activity, I was 28 then, I discovered Elias Canetti during a difficult time for me whilst in a strange place.

Where did it begin?

Auto-da-fé was an outstanding discovery for me. After, I read everything possible by Canetti.

What about required school reading?

I read everything from cover to cover. At the aforementioned Rakowiecka prison, I returned to many classics. It was there that I read the whole of Żeromski. Again, I had a lot of time… To my surprise, a great deal of Żeromski’s books turned out unreadable. You can return to Ludzie bezdomni (Homeless People), but things like Wiatr od morza (Wind from the Sea), Duma o hetmanie (Elegy for a Hetman), or Walka z szatanem (Fight with Satan) are a painful experience. Language is not the same anymore, and simply nothing matches our reality. And generally, I like Żeromski, he is not a writer whom I can disdain so easily. I’d like to return to Andrzej Strug, but I am afraid. The same with Wacław Berent.

When studying, I read Próchno (Rotten Wood) by Berent, and unfortunately his modernist language got very old. Strug, on the other hand, absolutely, you can read without concern, for example Dzieje jednego pocisku (The Story of one Bullet) or Fortuna Kasjera Śpiewankiewicza (Cashier Śpiewankiewicz’s Fortune). What About Popioły (The Ashes) by Żeromski?

It did not impress me even for the first time.

I have a weakness for this novel, maybe because of Wajda’s screen adaptation. Do you read contemporary Polish literature?

I am afraid of reading it, because I often feel it is a waste of time. I don’t want to list the names, since many of them are my friends, but most of all, I am afraid of factual errors. Embarrassing errors, especially when it comes to history. When I stumble upon them, I develop a bad attitude towards the book, and I do try to read with kindness.

Are you interested in reportage and non-fiction?

If nothing else, I read it as my work on the radio obliges me to do so. I keenly pick up books about mountains, since I was a mountaineer myself. I also read reportage and essays about culture. Sometimes only to confront what I witnessed myself. For instance, I am interested in Kurdistan, for I travelled ten thousand kilometres through Turkey. I slept on the roofs of Kurdish houses…

Do you read in foreign languages?

No, Polish is enough for me. I do sometimes take a look at the quality of translation, though. I am passionate about sports and when someone writes about basketball and they translate strike instead of shot, it throws me off-balance.

What would you recommend from sports books?

I happen to read biographies and books written by sportsmen, and I have to admit that there are not many books as interesting as the book by Andrzej Iwan.

Spalony (Offside). An extended interview conducted by Krzysztof Stanowski.

Andrzej Iwan is a guy who hit rock bottom. Perhaps this is why the book was so interesting, since sport is not really the most significant theme. As you can see, the spectrum of my reading is quite broad.

Science-fiction?

Not my cup of tea. I read maybe two books by Philip K. Dick, and only one by Stanisław Lem – Astronauci (The Austronauts), one of the worse ones, as claimed by the experts of his works.

Literature written by women?

I try not to make this kind of demarcation. If the book is a good one, it does not matter at all to me. I have recently read a historical novel by Sofia Oksanen from Estonia – very good literature. And the works of Carson McCullers, for instance, are one of the most remarkable phenomena in literature.

Best erotic writer?

Definitely Philip Roth.

And older things?

Markiz de Sade.

Since you mentioned Philip Roth, let’s talk about the Nobel Prize. Who out of the greatest has been unjustly overlooked in your opinion?

Milan Kundera.

Still alive.

Yes, but in my opinion, he has little chance of being recognised. I am glad that one of my beloved writers, Mario Vargas Llosa, received the Nobel Prize. I read every one of his books with fascination. And generally, from the Nobel-Prize winners, I value William Faulkner the most, he was probably the most prominent prose writer in history. Some of the Nobel-Prize winners, especially the most recent ones, I simply don’t know. And I don’t think I want to really know.

After Kazuo Ishiguro got a Nobel Prize in 2017, I don’t really know which direction the prize is going. What do you think about the recognition of Bob Dylan from two years ago?

Outright misunderstanding. It’s absurd, however, just to make it clear, I like Dylan as a singer.

Is there any award that you value the most and consider to be a good indicator for readers?

Yes, the Józef Mackiewicz Award (laugh).

That doesn’t count, because you are in the jury.

It’s good we have the Angelus Award. Regardless of the ugly story of casting Krzysztof Masłoń out of the jury, there were many good names that got distinguished. The problem with awards in Poland though is that they have greatly multiplied, and, at the same time, political divisions are transferred onto them. This is disastrous. Often, they are cliquey awards, which are only given to ‘their’ people. Another thing is that they are not really of high value in financial terms.

How do you take a break from words?

Reading never tires me. I don’t drive to work on purpose but commute from my Radość. It’s a part of Warsaw, but still a bit from the centre, so before I get to Polish Radio, I have 50 minutes that I use to read. I can’t imagine going somewhere and not reading.

What are you going to take with you on a holiday?

I don’t know yet, but certainly many fat volumes.

Interviewer: Marcin Kube

Translated by Justyna Lowe